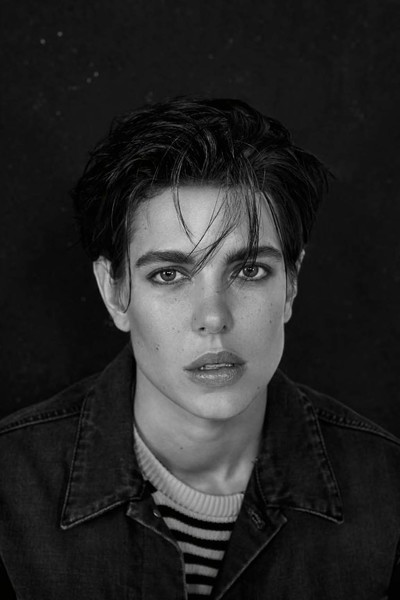

Charlotte Casiraghi mans up in this season’s Gucci.

Photographs by Collier Schorr

Styling by R.R.

Charlotte Casiraghi mans up in this season’s Gucci.

Photographer Collier Schorr arrived in fashion from a fine-art background, and it’s hard not to think that she brought some subtext with her on the journey. Because her fashion work delves deeper into its subjects than we’re used to, challenging and confronting constructed ideals of identity and beauty.

Today, Schorr moves between art and commercial work. Seemingly enjoying the contradictions and tensions of her dual practice, her work marks out a space in which she challenges how certain codes – leather jackets as tough; dark suits as inherently masculine – are made to feel natural by nothing more complicated than repetition. So what happens when you take men’s clothes that are already gender fluid – like Gucci’s recent menswear – and slip it onto a woman? Particularly when that woman is Charlotte Casiraghi, a Gucci muse, burdened by her own particular forms of coded expectation: she is the granddaughter of Grace Kelly, that archetypal Hollywood beauty, real-life princess, and the inspiration for Gucci’s 1966 Flora fragrance.

For Collier, the allure of that royal heritage was perfect material to distort, as seen in these photographs, shot for System in early September in Rome. The shoot, it turned out, was not only the perfect moment to take on gendered archetypes, but also the chance for a frank, involved and strangely seldom-witnessed discussion between photographer and subject. For Collier, the experience was rewarding: ‘I’ve never before felt the sense of collaboration so strongly with a subject – every photographer should do this.’

Let’s start with society’s shifting attitudes towards beauty, gender and identity. What do you think has shaped your attitudes?

Collier Schorr: I think I learned certain things from looking at pictures and the movies about ways I could be a powerful girl. And things that I could borrow from men portrayed as a certain kind of character. It seemed like I could just borrow the haircut or a jacket to build my own identity. You have to go back a long way to figure out what came first though: wanting to be somebody by copying something or naturally gravitating to something and picking it up, making it yours.

Charlotte Casiraghi: I think of the Simone de Beauvoir quote: ‘On ne naît pas femme, on le devient.’ Meaning that a ‘woman’ is something you become; it’s something you construct. We’re all made of biology, but culturally speaking, we have both the feminine and the masculine in us and in the mannerisms we pick up. It’s how you embrace both of them, picking up different postures from each that is interesting. That’s a more attractive idea, because then it truly becomes yours.

Define ‘attractive’. What do you consider ‘beautiful’?

Collier: I’ve always thought of beauty as something that existed outside of me. When I was younger, I always had a beautiful friend. And I realized that for years and years and years, if I had a beautiful friend, I felt safe with that person. And then I ended up in beauty as a job. I think that means I have a very different idea about beauty. I’m surrounded by the desire to kind of domesticate beauty, in a way, through working. I used to think that beauty was the thing that made life easier, yet it feels like it’s enjoyed by everybody except the person that has it.

‘I used to think that beauty was the thing that made life easier, yet it feels like it’s enjoyed by everybody except the person who has it.’

How do you think that your views on beauty might connect to gender? We often discuss them together, as if they’re inextricably linked.

Charlotte: They’re both uncomfortable. Because of what Collier just said, but also because, with gender, you sometimes feel people suffer from the separation of the masculine and feminine. That each of them, being mutually exclusive, does not fit with what or how they want to communicate about themselves. As if it’s dangerous to be both, or to let another one in. Maybe that’s why we see androgyny – you erase sexual identity by creating something that has no distinct sexual identity.

Collier: To address androgyny – or at least, what happens to me – I’ll see a boy wearing a lacy shirt, and I’ll be really attracted to that. I’ll want to wear that kind of shirt, because in my mind sometimes, I’m a boy wearing girls’ things. But the reality is that if I put something on, I’m not a boy wearing a girl’s shirt, I’m a girl wearing a girl’s shirt.

Charlotte: Often, we think we’re playing with the masculine and feminine by wearing certain clothes, by embracing certain stereotypes. The myth of androgyny that you see everywhere in fashion is women dressing more masculine or men dressing more feminine. Of course, a dress doesn’t just belong to a girl, and a suit doesn’t just belong a man.

Collier: I think language is really vulnerable right now. When you think about desire and identity, and you take the terms ‘masculinity’ and ‘femininity’, the complication is in the definition of what those things are. My ‘masculine side’ – what is that? Is that just an aggressive side, a tough side, an independent side? And my ‘feminine side’– is it just intuitive or sensitive? I think it’s always been this good-and-evil-type dichotomy. Soft woman, hard man. So if you present this masculine thing…

Charlotte: …that means you’re tough inside. We need reassuring symbols, like if a man puts a suit on, he’s assertive or he’s tough. Fashion has opened up the fact that you can have access to different characters by associating with codes aligned with certain genders or sexuality. It’s a symbol within a broader construction; it’s cultural. And it’s liberating, but at the same time it can sometimes block a deeper reflection on your own identity, because you can just take – copy and paste.

Collier: That’s probably why the most important thing in my work has been creating a kind of intimacy, making something intimate public. Because I think that people need to see images that have feelings, because they’re just inundated with artifice now that fashion is so much more accessible. I’m not saying that the feelings I evoke in my pictures are ones that come out of deep relationships, but they come out of the desire to be connected.

Did fashion play a part in shaping those feelings?

Collier: It did, I guess. I can think of a girl at high school who was two years younger than me, who I thought was absolutely beautiful, and I would dress like her in hopes that she would recognize that we were in some way ‘connected’. Of course, she never did. I’ve since learned that that’s a farce, but that’s what is sold to us in fashion. This idea that if you wear a certain uniform or a certain kind of thing, another person wearing that kind of thing will recognize that shared territory. Like, for gay men, in the 1970s and 1980s, that whole uniform became a coded language2 so that they could recognize each other in the streets. But fashion can also have the power to fuck you up sexually. Just looking at the way clothing is positioned and sold to us can make us either feel we can be anything or we’ll never be that.

Charlotte: You can reassure yourself with a style that you control, and control what other people see of you, and that’s great, but at the same time, it can be very imprisoning.

Collier: Everyone you meet, your body is immediately taking measure of their body. You’re figuring out who you are in that moment against an assessment of who they are. I remember that every gay person was called Boy George in the 1980s. It was kind of like, ‘Oh, hey, look at Boy George’. And of course, none of us look like Boy George, but it was a code for saying, ‘Oh, they’re so different from whoever it is I think I am’.

Charlotte: It’s exhausting trying to always send a clear message to other people. And I don’t necessarily need clothes to express certain things to the world. That’s why I sometimes like very neutral clothes. That’s why sometimes it’s just easier to pick up a white T-shirt and jeans.

Collier: I’m thinking that Charlotte and I are more aligned than not.

‘The most important thing in my work has been creating a kind of intimacy. Because I think that people need to see images that have feelings.’

Neither of you are particularly ‘girly’.

Collier: We’re both sort of comfortable being women, but open to and engaged with the attributes of men. And we’re both wearing a white shirt and jeans.

Charlotte: I do enjoy flowery dresses and prints though; things that might seem ‘girly’. But you’re right. I do really enjoy having the choice to embrace both. I find that to have both gives me so much more power of expression. I can wear a little floral dress or a suit and not feel as if I’m a different person or trying to enter a different character. I just feel that both of those are valid and a part of me. Going back to the subject of being inundated with clothes and fashion and images, I totally agree with Collier when she mentioned that fashion has taken a very strong place in society, not only as an industry, but also for young people in general. They embrace fashion much more than other generations. A kid today is more communicative in images than words, which, I find a little more difficult to deal with.

Why?

Charlotte: Because of that access to fashion, and having so many tools at your disposal to transform yourself to such an extent. It’s liberating, but at the same time, can make for caricature.

Where were you looking, in terms of references for your own gender and beauty ideals, at that age?

Collier: For me, when I was a kid, your aunt, Charlotte, was probably the quintessential… I kind of aspired to be that kind of girl, like I saw those pictures of her wearing shorts and a tennis shirt, and the haircut she had, and the kind of toughness that she showed. I think meeting you was in a way a continuation of that. You’re not your aunt, but it’s a continuation of a certain… I’m not sure, a curiosity that relates to surface. Intrigue.

Did that intrigue affect the way you prepared for this shoot?

Collier: For me, excitement before a shoot is when I’m already excited before I meet the subject. I’ve already created a connection in my head, and it was easier having looked at your aunt growing up. I think that has to do with being a kid, and looking at pictures, and feeling like I could know that person if I looked deep enough in that picture, and if I looked for enough clues. As a kid, I would collect pictures of certain actresses or models, because if I had enough pictures, it was like putting together a profile. I could start to figure them out. Still today, I really love being interested in the person I’m shooting.

What do Collier’s thoughts make you feel, Charlotte?

Charlotte: The fact that you’re not saying, ‘Oh, I think you’re that type of girl or woman’ or ‘you have a vulnerability in your eyes’ appeals to me. You’ve stayed very open while shooting, and I think that’s important.

Collier: I think that’s because I don’t want anything else beyond the emotional connection in the pictures. A picture or a sitting isn’t a means to something else, or proving you to be however people might imagine. And I think there is a fantasy about fashion photography as a kind of seduction. It is a seduction to get across a message; a seduction between two people who are kind of entering into this really vulnerable agreement, to look at each other, and to do this dance.

Is that vulnerability always there? Do you need confidence from a subject, as you would when shooting professional models?

Collier: No, because not everyone is confident. It would be really boring if, every day, you went to take pictures of people who thought they were amazing, and didn’t have any cracks or sadness.

Besides the element of seduction, what other dynamics arise when you photograph someone?

Collier: For me, photography is a really special way to spend time with someone, even if it’s complicated by the mechanisms of a sitting. It’s a really interesting process, because you’re with somebody who you immediately want to put at ease and comfort, but you’re putting them in a situation where it’s almost impossible for them to feel immediately comfortable. It’s like you go through this thing together, and hopefully end up in a place where it starts to just be a rhythm of understanding what the other person wants. I don’t go into a shoot saying, ‘Well, you have to be like this, because this is how I see you, and I want you to be like this’. We should only do the pictures you feel excited about doing. It just doesn’t make sense for me to force somebody to be someone they’re not. I also think that people play more when you give them the space to do so.

Charlotte: What I find interesting is that you can never see yourself as others see you. That’s what is happening right now: people with mirrors constantly in their faces or with selfies, constantly

trying to see or control the way they look in other people’s eyes. It’s quite new, but generally, you don’t really see yourself moving around in a room.

Do you enjoy looking at pictures of yourself?

Charlotte: I can feel surprised at having seen something that is perhaps fragile or strong, and then think that maybe other people see that in me. I might know it’s in me, but I don’t know if other people see me that way. But it’s important for me not to become too attached to the image or archetype, because I feel like I might lose my footing; and I feel like what I can build every day in my day-to-day life is more important, more valuable.

Do you enjoy allowing people to see this side of you?

Charlotte: I have no problem with people seeing me vulnerable. If I need to cry, I’ll cry, and I don’t feel uncomfortable if people see me like that.

Collier: Listening to Charlotte makes me realize how hard it would be for me to answer these questions. You could ask me, ‘What does it feel like to make a picture?’, and that’s a easy question to answer. But if you asked me what you’re asking Charlotte – what does it feel like to be in a picture or have people look at you in a certain way – then all of sudden, I’m flooded with a fear of narcissism. Flooded with fear of people looking at me or what it means to want to be seen. I always think that pictures of people, unless it’s a self-portrait, are about the combined interest in looking together.

Charlotte: But it has to be detached from yourself. I find it interesting if people see these pictures and find them beautiful, but I don’t want people to find me more interesting or beautiful because of the pictures. Just enjoy looking at the image because it’s beautifully photographed. I find giving importance to the image can give you confidence for a split second, but that’s it. It’s just about that split second and how you appear at face value to someone else.

Collier, does the so-called perfection expected, particularly in fashion, frustrate you?

Collier: I think luckily, it’s changed so much. Everything is sort of open right now. But I just want to go back to androgyny for a second, because I think for me, it’s always connected to men in a way. There’s a David Bowie situation. It always starts in my mind with a beautiful man who is so beautiful that he almost looks like a woman. For me, that’s a kind of target of androgyny, and so it is always wrapped up in beauty in my mind. And the only reason I care if it’s a boy or a girl is because I’m drawn to a beautiful face. I think the challenge that androgyny poses is a confusion for people – which is good. And going back to Gucci, in a way it’s good to confuse people to open up their idea of attraction, and self-expression.

Charlotte: I find that extremely liberating. If it becomes only a protection or rejection of your own gender, then it’s less interesting.

Collier: You’re not interested in angry androgyny.

Charlotte: It’s about being both at the same time, and that’s interesting, and not just being all or nothing.

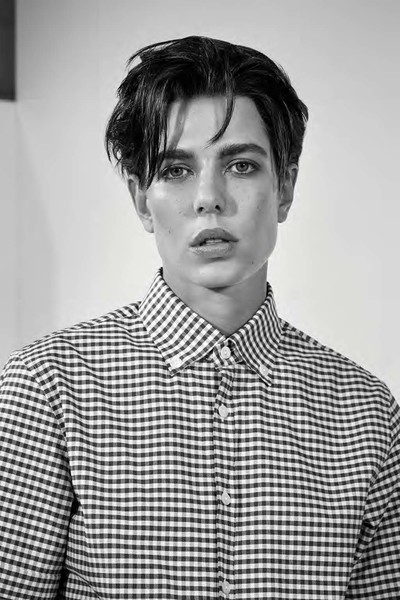

Collier: I don’t think that you’re number one on androgyny’s hit-list of targets. It’s not like you’re just waiting to made over into a man! You do fit into the history of pictures that I’m interested

in, though. You’re someone who’s not a reference; you’re not 50 years old, someone who used to be in pictures; you’re somebody who is now, and we’re in a different time. That was the excitement of putting us together, I think. It’s not recycling a cliché off the back of your family history; it’s actually just two women playing with picture-making and clothes.

Charlotte: Exactly. And the option of wearing a lace little dress or big, masculine trousers is the fun part of dressing up for me anyway.

Collier: I keep thinking, ‘I should just take a picture of her in that shirt, because it’s like a girl’s shirt’. But it doesn’t look that girly on you – clothes don’t wear you.

‘You have to trust the photographer, but also let yourself be transported by things you couldn’t predict or control.’

Collier, why are you interested in transforming Charlotte’s appearance?

Collier: I’m not sure I’ve actually transformed her appearance. I think I’ve just focused on ideas of how I think she thinks she looks. The sides that we’ve played with are there. It’s only that we’ve maybe highlighted something. I think we’re both interested enough in the identity at hand that we haven’t needed to transform it. I think any time that you put on clothes from a collection, you’re kind of fine-tuning something, playing with it a little bit, but you’re not turning it into something else. You’re not turning it into something that wasn’t there. That’s the exciting thing, I think. Ultimately, a transformation isn’t as satisfying as getting closer to the person.

Charlotte, what are your thoughts on the pictures, and what you’re aiming to do with this ‘non-transformation’?

Charlotte: I think I was just always trying to find a way of keeping something that was mine. I was willing to explore new things, trying to keep something that was real in me, and not just being an object of fantasy. I wanted to be a part of creating that fantasy while being connected to my feminine side, my soft side, and not just trying to force something just to surprise people. I don’t like the idea of being stuck in a box.

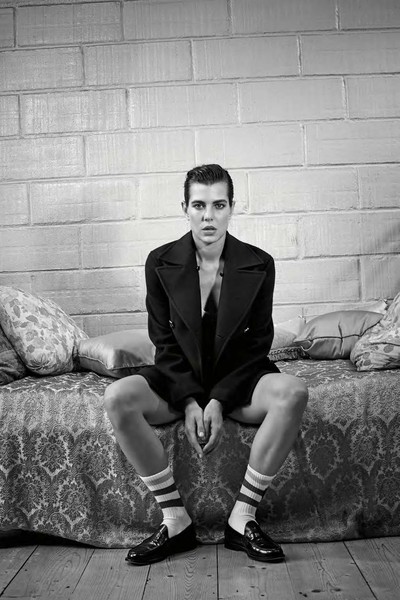

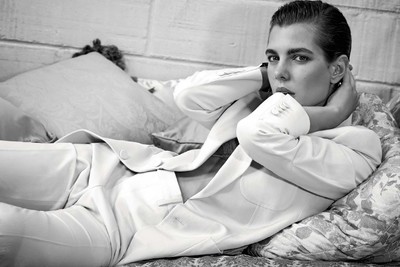

Collier: I also think it’s also important that, like you said, you’re creating. That’s what happens on a shoot: I’m looking, and thinking, and talking, and I have certain ideas about what happens if you sit down, or what happens when you stand up, but it’s you who is actually in control of creating the action, and opening up a character for me. Everybody is exposed in a picture, but then everybody has this sort of safety that it’s just a picture. There’s a real beautiful push-and-pull of vulnerability under the protection of ‘Oh, it’s a shoot’. But one of the reasons I really love fashion photography is because there is this potential to play with characters that can feel dangerous or troubling. That has to do with sexuality, making pictures that feel. I’m thinking about Balthus. And that little bed that we were shooting on, and how Charlotte goes from being a grown-up in a silk suit, to all of sudden the shorts and the socks. For a second, I felt like a voyeur.

You felt like Balthus for a second.

Collier: I did. But knowing what the other photographs were, and the way you were in them is what made me feel comfortable to do that, and I feel it was the same for you.

Collier, you’ve spoken in the past about the struggle between photographer and subject. What did you mean by that?

Collier: If I think about my initial pictures with German kids who didn’t speak any English, and I didn’t speak much German, there was always a sense of me as somebody who wanted something from somebody who wasn’t sure what I wanted. That’s my initial experience with photography. When I started, and the beginnings of shoots were hard, I would think, ‘Oh, well, this is just not going to work, and it’ll be over soon, and I’ll be sad, and I’ll go home’. As I got more practised, I realized that the introduction stage, like any relationship, is worth working through. The end result is worth working towards. It’s worth figuring out who you are around that person, who that person can be with you, and then making it.

Charlotte: So you like to collaborate?

Collier: I make a lot of room for people to say, ‘I want to play with it, but I want to play with it my way’. I can be a top or a bottom. I can follow a subject or I can dominate, but I’m only interested in dominating if that’s desired. And I think we really kind of danced around, and it’s really unique, this process, because I’ve never taken pictures with somebody where we were talking about the concepts the entire shoot. In a way, it’s kind of like an art project where there’s no naivety. You’re not going to just see what happens, you know what you’re getting into, and you actually have the discussion to strengthen your ideas. I think it’s important for someone who’s being photographed to be responsible for the pictures, too.

Charlotte: You have to trust the photographer, but also let yourself be transported by things you couldn’t predict or control – by feeling. Otherwise, you’re just letting them project their own fantasies on you, and where’s the surprise in that? I’ve always suffered from that, and at some point you have to be able to create fantasy and reality.

Collier: I think that we can’t lose sight of the idea that the excitement of taking a picture of somebody often comes from having seen other pictures. For me, I didn’t bring a fantasy I had based on other pictures I’d seen of you or your family. I just thought, ‘That’s somebody that I want to make a picture of’, because that’s somebody that I want to know. When you are a public figure, and a woman who is considered beautiful and treated as an object of beauty, it’s a kind of cage, and every photoshoot is either another lock on that cage or a way to open up the door. You just can’t know which until it’s finished.

Photographer’s assistant: Jonathan Ervin.

Digital tech: Stefano Poli.

Local photographer’s assistants: Edoardo Cafasso and Leonardo Damo.

Stylist’s assistant: Stephanie Kherlakian.

Tailor: Marloes Mandaat.

Hair: Ju (Shon) Hyungsun at Julian Watson Agency.

Make-up: Thomas de Kluyver.

Nails: Catia Piazza.

Production: Emanuele Mascioni at MAI London.

Props: Victoria Salomoni, assisted by Pietro Camacci.

Special thanks: Gucci, Studio Daylight Roma, Hotel Locarno in Rome, and Neela @ MAI Productions.