Colette founder Sarah Andelman and Dover Street Market boss Adrian Joffe on why the bricks-and-mortar experience is irreplaceable.

By Jonathan Wingfield

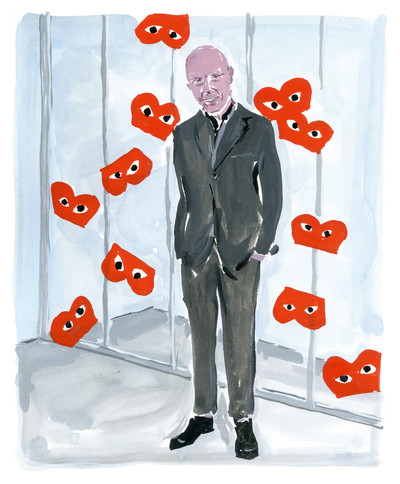

Illustrations by Jean-Philippe Delhomme

Colette founder Sarah Andelman and Dover Street Market boss Adrian Joffe on why the bricks-and-mortar experience is irreplaceable.

It was 1997. There was a Clinton in the White House, a Chirac in the Élysées Palace, and, not far away at 213 Rue Saint-Honoré, Sarah Andelman and her mother, Colette Rousseaux, in a soon-to-open store. When it did, on March 18, 1997, Colette changed shopping in Paris forever. Not only by redefining what a store should and could do – create, not capture, the Zeitgeist – but also by spearheading a transformation of Rue Saint-Honoré from ordinary, if centrally located Parisian neighbourhood into the city’s new nexus of luxury shopping.

While buying for the store, Andelman had approached Comme des Garçons CEO Adrian Joffe to see if he would allow her to stock the hallowed label designed by Comme creative head (and his wife), Rei Kawakubo. He saw the promise, said yes, and the label continues to be stocked today. Then, in 2004, the Comme couple decided it was their turn to create a ‘multiverse’ and opened Dover Street Market in London. Inspired both by Colette and legendary London ‘independent-trader’ hubs like Kensington Market, their vision brought together luxury and streetwear, rare books and perfume, coffee and watches. They have since spread the DSM concept to Tokyo, Beijing and New York, while the original Dover Street Market has recently upped sticks and moved half a mile across central London to Haymarket. Andelman, however, has refused to expand beyond her Paris base, figuring that those who can’t get to Paris can shop online.

Because in the 20 years since Colette opened, there has been another revolution. In the past decade, online retailers like Net-A-Porter and YOOX have created globalized virtual luxury worlds and opened new frontiers in retail. For some, this growth in fashion e-commerce brought into question the continuing existence – and even point – of old-fashioned bricks-and-mortar retailers. Why make people come to the products when the products can come to the consumer?

In reality, however, the digital revolution has, if anything, actually proved the value of stores such as Colette and Dover Street Market. Because in today’s market, offering products is the easy bit; what’s also needed is the intelligence, sensitivity and confidence to choose the right ones, and present them in new and exciting ways. In a world of always-on, instantaneously available pleasures, selection is differentiation, curation is distinction. And with that comes a shared shopping experience, a communal moment. So on a sunny late-summer afternoon, we brought Andelman and Joffe together to talk retail today, the blending of the virtual and physical, brands and ideas, and streetwear and luxury, in the place where it all began: 213 Rue Saint-Honoré. Colette.

‘The idea of everybody staying at home and buying everything they need online is very melancholic, very depressing.’

Jonathan Wingfield: Let’s start with an obvious question – what is your definition of a good shopping experience?

Sarah Andelman: If you know what you’re looking for, then a good shopping experience is one where you’ll find that thing, your size is in stock, the experience is quick and efficient, and you leave a happy customer. But just looking around can be the best shopping experience. I love the idea that people come into Colette convinced they won’t buy anything, but then discover something unexpected and can’t resist. We have so many different products and options that anybody coming in just out of curiosity can fall in love with the music or the in-store fragrance or a new pair of sneakers.

Adrian Joffe: When we started Dover Street Market, we didn’t want it to be a Comme des Garçons flagship store. We thought we’d try something new that would give people a reason to leave the house, because bricks and mortar – actual physical places – are fundamental to the survival of shopping. Then Rei and I started thinking about markets like Kensington Market, which we’d always loved, because the energy of the marketplace is so exciting. The idea of everybody staying at home and buying everything they need online is very melancholic, very depressing. As Sarah says, it’s about offering something to discover, an adventure, some excitement. People can spend all day at Colette or Dover Street Market, or just pop in to buy their favourite perfume.

What about your own experiences of shopping? Do you have particular childhood memories of a market or a shop?

Sarah: I remember, in the late 1980s, early 1990s, my mother taking me on a pilgrimage every Saturday to Comme des Garçons on Rue Étienne Marcel. Everything about it was amazing: the store design, the clothes, the staff.

Adrian: Wow, was that really your first memory of shopping?

Sarah: Well, the very first was like everyone else’s: buying colourful candies at the boulangerie before or after school. But as a teenager, before I moved into Paris, we would come to Étienne Marcel,

Rue du Jour, the agnès b. store, because the suburban shopping experience where I lived at the time was limited to Parly 2.2 I was probably the only kid at my school who knew about Comme.

Adrian: My parents had no idea about fashion. My mum would just take me to Marks & Spencer or Selfridge’s food hall in London. But I remember getting a little interested in fashion when

I was about 14 or 15; there were a few Italian shops on the Fulham Road, and I remember going in this tiny multi-brand store and seeing a ripped jumper with a suede elbow and dreaming of one day being able to afford it. And when I actually went in and bought it, it was very, very exciting. But these days I don’t ‘go shopping’, in that sense.

Sarah: The shop where I now spend the most time is Amazon! I’m as thrilled as anyone else when things arrive 48 hours later; I find it fantastic. Adrian, were you serious when you said you no longer

do any physical shopping?

Adrian: I still like to browse in bookshops. When I travel for work, I’ll make a point of popping into all our stores, and the multi-brand stores that buy us, too. But in terms of actual shopping, I do it all at Comme des Garçons. Anything we don’t sell – like underpants, or swimwear and so on – I just buy online.

It’s ironic that you used the term ‘browse’, because it’s one that’s long been appropriated by the digital world.

Adrian: It’s a nice term, and I think the notion of browsing, in places like Colette, is really important. Life can be very lowest-common-denominator these days; you’re almost told what to get, what’s in, what’s now, what’s trendy, and you don’t really decide for yourself. There is less autonomy, less self-generation of your own expression, and that is why browsing is perhaps more important than ever. I think Colette and Dover Street do that in different ways, but we both give people options and alternatives. I think it would be very sad if that all went away.

Sarah, you made shopping on Amazon sound like a guilty pleasure. Why are online shopping experiences seen as soulless, whereas buying, say, one-off slippers in a Tangier souk, has become this almost mythical and fetishized ‘authentic experience’?

Sarah: For sure, online shopping is less interesting because it is experienced behind a screen as opposed to real life. But I’d say any feelings of guilt probably come from the fact that my life at Colette has always been about showing how the bricks-and-mortar experience is irreplaceable, and a model that will continue forever. We’re not proud to buy online, but today it’s vital; there are some things we can’t even get in physical shops anymore, so you can’t fight it, you have to go with it.

Adrian: Maybe one feels guilty about denying oneself the chance of that authentic memory in the souk, but I don’t think anyone really feels that guilty about online shopping.

Sarah: It’s funny that you mention slippers in Tangier souks. I went there and found these wonderful little orange-blossom perfumes. We’re really proud to be selling something that normally

you would have to go to a market in Tangier to get.

Adrian: If customers know that story, and know the origins, then I think they can at least glean some kind of pleasure. That is what it’s about, providing that service.

Sarah, talk us through the events that led up to you opening Colette in 1997.

Sarah: I was studying art history and my mother had her shop in the Sentier, but she had always wanted us to work together. We moved into an apartment in the very same building we’re in now, and every day we would walk past the empty white space on the ground floor, which was for sale.

How was the neighbourhood around here at the time?

Sarah: Very different then; typical neighbourhood shops like the butcher, the fishmonger, a news stand. The fashion stores stopped before you got to Rue Royale and Place Vendôme, just after Hermès on Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré. And then at the opposite end, you had Les Halles, but right here was a bit of a no man’s land, with nothing apart from, ironically, the Comme des Garcon offices on Place Vendôme! How come you ended up there?

Adrian: Somebody recommended that space on Place Vendôme when we first came to Paris. For Rei, a Japanese woman coming to visit, we had to be in the very heart of town, not somewhere in the 18th or the 11th arrondissement. That was very important. Was it important for you to be in the centre?

Sarah: We didn’t really ask ourselves the question; we just visited the space and fell in love with it, and the way the light filled it. Mum immediately had the idea that I should present exhibitions and show young designers here. Paris was pretty quiet at the time and we loved the idea of bringing different worlds together in this one space. The slogan at the start was ‘styledesignartfood’, and it was vital that we didn’t limit ourselves to a single domain. The other main intention was for continuous renewal.

Did this idea seem at odds with what was happening in Paris at the time?

Sarah: Right from the start, there were people who followed us, and others who were like, ‘Oh là là, it’ll never work; they’ll close in two years’. As I mentioned, not a lot was happening in Paris at the time; the interesting stuff was in London, with people like McQueen and Hussein Chalayan.

Adrian: There really was nothing like Colette in Paris; there was nothing like it anywhere.

Sarah: Adrian, I don’t know if you remember us coming to see you. We must have been so young, probably only 19, I think. I don’t know what you thought, but for us, having Comme was a really, really big deal.

Adrian: It all felt like such a new thing, and I recall you really wanted us there. I don’t think it took long to convince me.

Sarah: So much of what we wanted to present were things we couldn’t find in Paris at the time. I always use the example of the beauty brand Kiehl’s, which was only sold in New York back then, in the original store run by the family. We’d just think to ourselves, ‘Why isn’t that stuff sold in Paris?’ The same thing occurred everywhere – a pair of Reeboks or a G-Shock watch that you could only find in Tokyo. So there was always this sense of excitement when we travelled to New York or London or wherever, and saw products that we’d bring back to Paris.

This leads into my next question about curating. The word ‘curate’ actually comes from the Latin word curare, which means ‘to take care of’, but today, curating is more a question of expressing an opinion or an identity through the act of selecting and assembling choices. I presume many people consider your work at DSM and Colette to be a form of curating…

Sarah: The term that used to be thrown around a lot – less so now – was ‘concept store’. I used to hear that all the time and would find it rather patronising, whereas curating is associated with galleries and museums, which I find quite chic! It is genuinely what I do. Twenty years ago when we’d select pieces from Comme des Garçons, and now when we discover an artist in a gallery or products from beauty brands we’ve come across.

Is it all you as an individual?

Sarah: It really is me who does it; we are not like a department store where they’ll be a team of 15 people analysing their footwear sales on big charts and so on. I can look and choose, I select and then I follow up the arrival in store. I make sure that it is well presented and well integrated into the shop, and then I wish it a good life! I’m simplifying, but that is pretty much what I do.

How would you define the selection process?

Sarah: Colette is like a puzzle that needs the right pieces to fall into place, or like a cocktail with the right ingredients. That’s the impression I have of what I do: I choose and edit things from a thousand different brands and places, and it’s about getting the right puzzle, because every single little product in the store is there for a reason.

So the physical mix is as important as the selection.

Sarah: That is what differentiates us from the department stores, where you have a brand with its corner [concession stand]. One of the essential differences between Colette and Dover Street Market is that we mix everyone up – say, Comme des Garçons, Gucci, Simone Rocha – and every week we change that mix, to create new associations. So everything has to go together, even if it’s only us who notices it.

Would you say you actively look for trends?

Sarah: I don’t know what trends are; I think I just manage to capture an air du temps.

Adrian: Do you ever get anything you don’t like because you think it’s the right thing to do for your customers?

Sarah: No. Never. What about you?

Adrian: Oh, there’s loads of stuff I don’t like in my shops! [Laughs] I mean, we work with a team now, and there are four big shops and I sometimes get defeated. I’ll be like, ‘There is no way I am having that shit’, and they all say, ‘Yeah, but it’s going to sell well, and it’s cute and nice’, and so I end up saying, ‘Alright, if you insist’. It’s a bit looser than with Sarah; Sarah really is one eye. She is the same as Rei. That’s why Rei has a heart attack when she comes into Dover Street because there are loads of things that she’ll look at and say, ‘What’s that doing here? What did you get that for? Why did they put that chair there?’

Nonetheless, I get the impression that Dover Street Market is very much your baby.

Adrian: Ten or 12 years ago there was less going on, so Rei would help me more with Dover Street Market. These days she just takes care of the visuals and building up the design elements; we try to keep her informed of all the other content, but basically Rei has left it to me. It has become more and more my thing, which Rei finds really hard because she wants to do everything, but she can’t do everything, and she knows that.

What about selecting of the brands?

Adrian: Whenever we can, we’ll have meetings with Rei about which brands to buy and how to put them together; her instincts are always crucial and we couldn’t do it without her being there behind us, like some kind of ether.

Would you say there is a big operational distinction between the Comme des Garçons stores and DSM?

Adrian: Comme des Garçons is always perfect because it is Rei’s eye: every shop, every garment, everything that she does is perfect for her. But a lot of the things in Dover Street, she says, ‘Why did you do that?’ But that’s OK because the concept of Dover Street is to make mistakes.

Dover Street Market feels less about curated products like in Colette and more about constructing a kind of marketplace in which the Comme world can exist.

Adrian: It’s the same in terms of always wanting to offer new things and new juxtapositions of things. But we give a freedom of expression to people who somehow share something, some value; they all have a vision and they all have something to say. For me, that is enough, even if I don’t necessarily like what it is they’re saying. The clash of expressions – ‘the chaos’, as we like to call it – is interesting.

‘Rei has a heart attack every time she comes into Dover Street because there are loads of things that she’ll look at and say, ‘Why did you get that?’’

Would you say your role is to offer a space for the brands – regardless of their respective scale or resources – and encourage them to do something different?

Adrian: That’s exactly it. Big multinational groups want to be in Dover Street because we give them a chance to express themselves differently. Every shop those big brands have might be identical, so when they come to us, we say, ‘Don’t spend £50,000 on your space, spend £10,000; do something small, something temporary, free yourselves up, you can change’. So they get all excited… and then just do exactly the same thing! We have to politely suggest to them that maybe there’s no point them being in Dover Street. I mean, if what they’re proposing is really too boring, it’s not good for anyone. But that’s always a hard conversation to have with some people.

You think some of those brands are missing the point?

Adrian: Totally missing the point. They try, they really try, but some just can’t deconstruct, usually because there are too many suits in the way, so we part ways as amicably as possible.

Collaboration is ingrained in what brands do nowadays, especially in the digital world, and it feels like both of you have been embracing that shared experience for years.

Adrian: Rei has always said she feels lonely out there on her own, trying to do something creative. She has always had this very un-egotistical attitude and that’s why she loves the idea of Dover Street because she can share the space with like-minded people, in order to present new things, new ideas.

But few people, for whatever reason – usually commercial – are able to continually create newness to the extent Comme des Garçons has.

Adrian: Rei always says, ‘Why don’t people work harder? Why is this the same as last year? Why does the show look the same?’ But when someone does something different she really

acknowledges that, and she is really inspired and excited by the idea of Dover Street somehow promoting new ideas. And you’re right, I think we did start that idea of brands sharing a space. Fashion people in general are very protective of their own territory – you don’t share things at all – and I think that has changed, partly thanks to Sarah and me, because we’ve opened up opportunities for so many people.

The flipside to all this shared experience is, of course, the increased need for everyone to have exclusive products, exclusive content, exclusive timeframes. How important is it to you to be selling products exclusively?

Adrian: My team really like and want exclusives, but I’m always saying, ‘Look, we can’t guarantee these poor brands so much money; I want to try and see how it works, and if they want to sell to other

stores then that’s OK’. To be honest, it’s not as vital as people make out. It’s not fair either.

Sarah: I agree with Adrian. A young designer won’t say to us, ‘We’ll only sell to you’. It’s up to us to get our customers to buy it from us rather than the next shop. There are lots of young designers who ask us, rather sheepishly, if they can also sell to department stores in Paris, and although I suspect people think otherwise, I always say yes.

Adrian: Me, too.

Because it’s good for business?

Sarah: No, because they need to be able to develop.

Adrian: It’s a fine line between protecting them and suffocating them.

Sarah: But sure, it can be good for business, too. For example, Le Labo, who we’ve had exclusively for a long time, just opened up nearby, but we haven’t stopped selling its products, because we have a loyal clientele. Although that’s perhaps where beauty differs from fashion. We have lots of brands with their own boutiques in the area. It’s good for them to be seen with us, and we do a massive job in terms of explaining and promoting their products to our customers. Ultimately, it’s important for us too that, as a brand becomes increasingly established, it is known beyond just our walls.

People generally go to Dover Street Market for the Dover Street Market experience, not simply to shop for a particular brand or particular product.

Adrian: I think that’s true.

Sarah: I think perhaps street culture is the exception. With Nike, for example, you really have the sneaker-head collectors. At Colette, sneaker launches are on Saturdays at 11am, and the sneaker-heads are already there in front of the shop; they know what’s available exclusively at Colette. The day they are exclusive at NikeLab,6 then they go to NikeLab. Thankfully we don’t just have that, but in that scenario we are dependent on the brand.

What about that whole culture of people queuing outside shops to get limited editions? It feels like FOMO culture – Fear of Missing Out – has become a ubiquitous marketing device.

Adrian: Some brands certainly deal with their market like that; they control surreptitiously and it’s all about reselling. I guess you just have to tread a fine line; we try to get the fans, not just the resellers, and we tell people who really love the product to come early. We know the resellers, we know who they are, but you can’t stop them. It’s a very interesting phenomenon and you’re right, it’s an important part of that world today.

Let’s just go back to the subject of cohabitation within your shops. Like everything else in fashion, doesn’t that become a huge political issue?

Sarah: We put everyone on the same level, whether it’s Gucci or the up-and-coming designer.

Adrian: It’s very egalitarian in a way.

Sarah: We’ve said from the beginning that we want the customer to be attracted by the clothes themselves and not by the brand. Of course, the brand is important, but what really counts is the final product in front of you. So that’s why we put them all together in this sort of forced cohabitation.

Adrian: We keep the visual identity of some of the brands, but we mix everything up, too. For the first five years everyone was saying, ‘This isn’t going to work. Where is the menswear? Where are the shoes? Is this the expensive section? Is this the cheap department?’

Do the luxury brands have a problem with the fact you are selling £50 T-shirts around their spaces?

Adrian: Never… OK, sometimes you might get a little bit of friction. A classic example for me was with Supreme and Prada. When we opened Dover Street Market in New York three years ago, it came across like we had maybe bent the rules for Prada because their space appeared to be going round the lift, and invading about 10cm of the Supreme space. James Jebbia of Supreme7 went absolutely ballistic: he wanted to leave, and was like, ‘Why didn’t you tell me Prada was coming here?’ And we said, ‘We don’t tell anybody who’s next to who, that’s the whole excitement and surprise’. Ultimately, James Jebbia loved being next to Prada; it took him a couple of days of moaning and groaning, but he’s an amazing guy because he got it in the end. I mean, Prada has gone, and it’s Gucci now, and he loves Gucci even more. Similarly, others might not love being next to Supreme, but Gucci, for example, love it.

Sarah: These days, the same client would buy both Gucci and Supreme! It works for both of them.

Adrian: That is exactly what Alessandro Michele loved about being next to Supreme; the possibility of someone buying a jacket from him and a sweatshirt from Supreme. It all goes back to the idea of curating.

How well do you think you know your customers?

Sarah: When I walk through the store and see people from all horizons – including people who might have no interest in fashion but who are looking at the books or the music selection – I feel really lucky to have that diversity.

Adrian: I know our clients who come on a regular basis. What pleases me the most, like Sarah says, is seeing all the different kinds of people. I always want to get the attention of the Middle Eastern ladies, but they keep themselves to themselves; then there are the Chinese customers who I’m sadly not able to really interact with because of the language barrier. And then there’s the actress Una Stubbs in London, who pretty much comes every other week. Una has a browse, occasionally buys a T-shirt, comes upstairs to have a coffee and a cake, and then goes. She just loves being there. She’s nearly 80 years old, and is the most amazing lady, and one of my favourite clients.

Sarah: There are the people who come specifically to Colette, and others who are walking down Faubourg Saint-Honoré or have been to the Jardins des Tuileries, and just step into this bustling

shop they’ve maybe never heard of before. When we first opened Colette I heard people say they were scared to come in because it looked so stark, like a gallery or something. But we opened the ground floor up to sell books and magazines to make it feel less intimidating, and these days you’ve got €1 bracelets there, too.

‘James Jebbia of Supreme went absolutely ballistic: he wanted to leave Dover Street, and was like, ‘Why didn’t you tell me Prada was coming here?’’

Sarah, how do you maintain momentum when you restrict yourself to just the one shop in Paris?

Sarah: The facade might not change, but we constantly change everything inside. If you look at photos from a couple of years ago, the tables, chairs, lighting and the way we organize the space has all changed, not to mention the displays that we change every two weeks.

Adrian: Do you realize that Sarah, herself, has done 2,000 windows at Colette? I’ve just done the calculation. Every week she changes the window: 52 weeks of the year times 20 years. That’s one way she keeps things new. No one else in the world does that.

Sarah: We have always done those things, but people only really realize now thanks to means of communicating such as Instagram. Today, it’s the turnover of the broader fashion market that is more important: how the brands now do two, four, six collections a year, and how small streetwear brands will produce new items every month. We are constantly bombarded with new products, so that rhythm of reception, sales and moving onto something else is more rapid than ever before.

In what ways are you now aware of the consumers’ wishes and expectations?

Sarah: We try to meet our clients’ needs, but it’s good that they are more and more informed, that they know about the existing designers and brands.

Adrian: I think we’ve become a little the victim of our success – we’ve taught people to expect different things all the time. Before, they’d come in and say, ‘Oh, that’s different’, but now it’s more like, ‘OK, so what’s different today?’ It’s the treadmill that you have to stay on these days, and do it quicker or better or have more of it.

Is Rei still reluctant to engage in e-commerce?

Adrian: Yes, she doesn’t like the idea of the main Comme des Garçons line being sold online because she wants people to come into the shops, try it on and touch the fabric, and talk to somebody. Our customers like Sarah all sell Comme des Garçons online – I’m not actually sure if Rei knows about that – but we can’t control that; it’s too big. I mean, they could put it on a rack outside and sell it at whatever price they like; there are some things you simply cannot control. Rei has accepted the online selling of things that are perennial – like [the Comme des Garçons line] Play, the wallets and the perfume – and we’ve got all the other brands on our e-comm, and it’s unbelievable how well it works, but it could be so much better if we sold Comme des Garçons, too.

What percentage of sales do online sales now represent for you?

Adrian: Maybe 10 percent. It’s very small, but that 10 percent didn’t exist before, so that’s still £3 million.

Sarah?

Sarah: I don’t know.

Adrian: It must be 20, 30, 40 percent?

Sarah: Yes, something like that.

Adrian: But Matches is like 95 percent. I think Ruth Chapman is a genius, but what works for others doesn’t always work for us.

‘Why do we always want instant gratification? Why do we want to see something in a show and buy it the next day? I can’t stand the idea of see-now-buy-now.’

Do you find it difficult to keep up in a system that is so governed by speed? Amazon is planning to drone deliveries, Net-A-Porter’s ad campaigns are all about getting a new outfit delivered before 5pm…

Sarah: We do the best we can. If you order before midday, you can get your purchases the same day, before 7pm – that’s our ParisExpress service – but we don’t advertise or message it in the same way as Net-A-Porter. But we obviously have to keep up; I myself am the first person to want everything quickly.

Adrian: Personally, I don’t like it. I think it’s something we should resist. Why do we want instant gratification all the time? Why do we want to see something in a show and then have to have it the next day? That’s why I can’t stand the see-now-buy-now idea; it’s not good.

Sarah: I don’t know if it is instant gratification.

Adrian: It is! You want, want, want; you need, need, need. Well, you don’t actually want it; you don’t actually need it. No, you’ve got to wait: you read about it a bit, you see a review, you see it in advertising, and then six months later, it’s in the store. Yes, I’ve waited – there’s the excitement!

Sarah: I think there is a difference between the professional and the personal: I find it dreadful that people expect an instant response any time they send you a text or an e-mail. But for a material product – especially books or music that you can have straight away – that seems quite normal these days.

But you guys still survive as physical shops, in spite of a digital revolution. Does the physical experience still override the online one?

Sarah: For us, yes. You come to Colette and it’s not just about shopping; there’s a gallery, you can have a coffee, it’s a place to meet up, to be inspired. If it was just limited to selling products, I could obviously understand the move to online only, but it is more of a living area than a simple store.

Adrian: It’s absolutely 100 percent our raison d’être to offer that; it’s almost cultural and social. If we didn’t think people needed it, we wouldn’t be here.

Do you think it will continue to grow?

Adrian: A couple more stores, maybe. I mean, who knows how big we will get? I’ve always admired and been amazed by Sarah for not wanting to do another Colette anywhere else.

The question I often ask CEOs is, ‘When is big too big? When do you stop growing?’ And Colette is like an extreme version of resisting expansion.

Sarah: People must think we’re crazy! But we are so dedicated to the little details that we couldn’t imagine technically doing anything bigger, or elsewhere. Above all, we really did open this just for Paris, to fill a gap here.

Do you not take up these offers of wonderful data analytics?

Sarah: My mother’s always been in retail and even though it was different before, she often said, there’ll be a season when everyone wants a blue dress, so you naturally go and buy lots of blue dresses for the next season, and then no one will want them! And she’s right, especially with the current speed of things. I would prefer to miss the trend than become a slave to analysis!

Adrian: But it’s a huge business, and brands like Zara that appeal to the majority of the population are totally dependent on these things. We need H&M, we need Zara, and if they do good collections based on analysis, that’s OK. It creates work; it feeds people; you can’t denigrate that.

Adrian, you’ve often talked about the importance of location. With the need for authentic shopping experiences to counteract e-commerce, is destination shopping having a resurgence?

Adrian: It’s useful to be in the centre of town because you’ll go for a meeting, or have a lunch somewhere, and it’s like, ‘Oh, Colette is nearby we should pop in’. That’s especially true in London, where it takes you an hour and half to travel to east London. But we’ve never been able to afford certain places, and I don’t think we’d fit in those upscale locations anyway. The original Dover Street was kind of cool because we were two roads away from Bond Street. Haymarket is now even more central, but it’s still a bit ‘off’ in terms of supposed great retail locations. I think maybe we lost five percent, but we’ve got a lot more new customers, which is great.

Sarah: So what’s the future for Dover Street Market?

Adrian: We’ll open in Singapore next year. Beyond that, we’ll see. I’ve got incredible teams in New York, London and Ginza that I’m already training here in order to take over, as I’m not going to be doing this all my life. It will be nice to be attached to it, but not have to worry about it. I don’t think anyone could imagine Colette without Sarah, so when Sarah goes, Colette goes. But change is a good thing.

Sarah: That’s all true, and I just realize how lucky I am to be in this position. The freedom from not needing to report to anybody is such a privilege. I don’t have to justify my choice to anyone. I am so lucky in that respect, and I don’t take it for granted.

Adrian, you said earlier that you have great respect for what Sarah has done. Did that influence your decision not to open in Paris?

Adrian: Completely and utterly. There is enormous respect between Sarah and me and Carla.11 We have this tacit agreement in which we’ve split up the world. Sarah is in Paris, so I don’t think Carla or I would dream of coming here. Carla’s got Milan, Seoul and Shanghai; I wouldn’t go to those places and she wouldn’t come to Tokyo or London or New York… or Singapore! One day we should all do one together.

What is the common ground between Colette, DSM and Corso Como?

Adrian: I think we share a lot of qualities, from working with our hearts and minds and souls and giving everything. But I don’t think that Colette would be so great in London, and I don’t want a Dover Street in Paris, because Dover Street was really born out of the idea of those great London markets from the 1960s and 1970s. Colette came from a lack of anything interesting happening retail-wise at the time in Paris.

What is the most revolutionary thing that one could do in retail today?

Adrian: We still are being revolutionary, we always will be; we just need to keep on going.