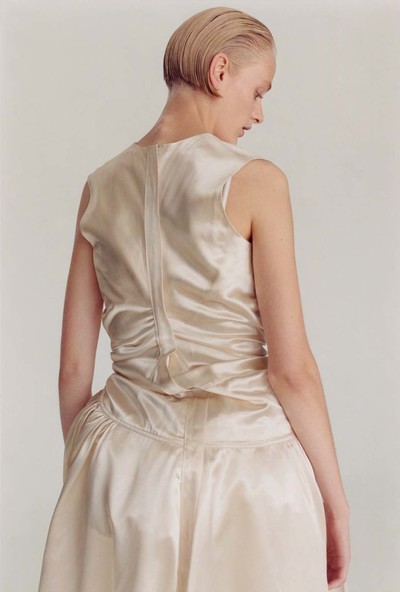

Why a vacant stare is the look du jour.

By Alexander Fury

Photographs by Zoë Ghertner

Styling by Marie Chaix

Why a vacant stare is the look du jour.

You know the look: blank-eyed model, jaw slack, pupils dulled. You see it on all kind of faces, staring vacantly from the covers of magazines, or even in person, as models perambulate in varying states of undress through the four fashion capitals. Backstage, behind the scenes, these young women are alive, dynamic, vibrant. They want to be doctors and writers, maybe actresses. They want to save the world. But when they’re working, they disengage; they become passive and receptive. To paraphrase John Berger, they do not look – they watch themselves being looked at.

OK, I know I’m a man, but hear me out.

It isn’t a notion particular to the model of today. As Berger suggests, the passivity of the female gaze has characterized our consumption of imagery for centuries. ‘Men act and women appear,’ asserted Berger in his landmark 1972 book Ways of Seeing. Which perhaps sounds like rubbish. But how true is it when Berger asserts that: ‘A woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself. Whilst she is walking across a room or whilst she is weeping at the death of her father, she can scarcely avoid envisaging herself walking or weeping. From earliest childhood she has been taught and persuaded to survey herself continually … Her own sense of being in herself is supplanted by a sense of being appreciated as herself by another.’ For a model, that is not only her life, but her livelihood.

Fashion is often pilloried for being superficial. Which is understandable. Fashion is about looks, of course, about refashioning outward perceptions of your body through the garments on your back. But it is also, fundamentally, about sensuality – the touch of fabric, the feel of a garment on the body, the transformative effect of physical contact between us and it. Occasionally, one is subjugated for the other: the comfort of the track pant versus the discomfort of the corset. Feeling good versus looking great. Yet when ‘fashion’ is discussed, it is often reduced to the purely visual. That is also the fault of the industry, in part. Many people cannot afford fashion; many garments will not, ultimately, be manufactured or sold. The ephemerality of fashion is frequently only captured for posterity by imagery. Unlike food, which has to be digested to be truly appreciated, fashion can often be devoured by the eye alone.

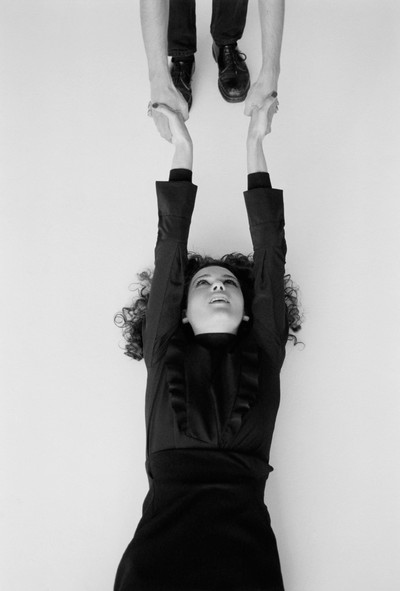

Laura Mulvey, in her seminal text ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ (which applies to still as well as moving images), reasoned that women are constantly diverting their own eyes, facilitating their status as the object to be looked at rather than the subject doing the looking. Again, this is part and parcel of the job for a model. A certain objectification of their body is inherent: a model will speak of the obstinacy of her waist in yielding to a tightly cinched dress or the ability of her feet to ram themselves into shoes very many sizes smaller than they should be. Of course, women (and men) often objectify and analyse their appearance – but seldom with the bald functionality of a model, who knows the limitations of her body the same way a mechanic knows a car. A body is a model’s tool of the trade – ‘a functional object’, as Jean Baudrillard described it in The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures.

Ironically, for models whose images are presumably manufactured for consumption, their look frequently comes across as unapproachable, haughty, aloof.

Perhaps that accounts, in part, for the detachment of a model’s gaze from the magazine page. Berger sees women objectifying themselves; Baudrillard reasons that model’s bodies become objects. And, technically, the magazine page – or, indeed, the tainted canvas – transforms the body into an inanimate object, one that can be manipulated, manhandled and even destroyed.

But the passivity of the female gaze in fashion imagery is often accompanied by a degree of ennui. Which can be interpreted differently. Models gaze not with passivity, but with disinterest. If they are watching themselves being looked at, they are doing so dispassionately. The seductive gazes of the past – what Baudrillard calls, ‘Medusa eyes … these fascinating/fascinated, sunken eyes, this objectless gaze – both oversignification of desire and total absence of desire’ – have been superseded by passivity, pupils barely flickering over her viewer. In contrast to the pornographic actor – to whom she is frequently compared – the fashion model doesn’t purport to be interested in her observer. Nor herself. Nor anything, really.

That wasn’t always the case. Fashion and pornography once made uneasy but natural bedfellows. But just as the bodies of pornography differ vastly from the bodies of models – both are functional objects geared to elicit desire but, presumably, not in the same audiences – so do models’ gazes. Pornography still beckons viewers in, to join and enjoy, openly indulging scopophilia. The fashion image, however, is remote and removed, perhaps to better adhere to the old adage that we always desire most that which we cannot possess.

There’s another notion, of course, that blows Berger’s assertions apart when applied to fashion. The primary consumers of female fashion imagery are other women. In her essay ‘Fashion and the Homospectatorial Look’, Diana Fuss argues that fashion photography is primarily focused on the consumption of a female model by female viewers. ‘The fashion industry operates as one of the few institutionalized spaces where women can look at other women with cultural impunity,’ she asserts. ‘It provides a socially sanctioned structure in which women are encouraged to consume.’ Heterosexual women admire models, generally, because they want to be them, in some way – acquire their life, their looks, certainly their clothing. Heterosexual men admire women because they want to have them.

That is about examining the gaze of the onlooker, which, whether male or female, reduces the model to an object, to the status of the observed. But what about the gaze of that model? The idea of her as an active participant in an exchange? A model is not unaware of her own image – she is no mere Trilby manipulated by her Svengali. What really is the effect of her female gaze?

Ironically, for models whose images are presumed manufactured for consumption, the look frequently comes across as unapproachable, haughty, aloof. Connected, once again, with that idea of the unobtainable. The body of the model can never be achieved, particularly because of fashion’s current, overwhelming focus on youth. While fat can be suctioned and curves enhanced – they’re directly adjustable – youth can only be imitated, never attained. Time is a precious commodity, for more reasons than one. The young fashion model stares with a look of detachment and slight disdain, daring us to desire what we can never possess, what she has: her youth.

What else does she possess? A dress that may never be made; a jewel we could never own (but neither could she). In that respect, the contemporary fashion model is linked to grand Renaissance portraits. Like Bronzino’s 1545 portrait of Eleonora of Toledo, whose sumptuous gown is thought to be a figment of the artist’s imagination, based on a fragment of rich fabric. The fantasies depicted in Renaissance art were intended to confound and impress rival families, to speak of the real riches of those portrayed, and possibly to exaggerate them to even more fantastical proportions. The same doublespeak takes place in a fashion image, where the models clutch handbags of exorbitant price and limited availability, dressed in furs, coldly glaring at us from their finery.

Like the fantasies depicted in Renaissance art, models clutch handbags of exorbitant price, dressed in furs, coldly glaring at us from their finery.

There is, of course, the notion that the gaze of the model is neither disapproving nor desirous, but simply blank. Vacant. It is the idea of the model as seen through her French name: mannequin. The model as an artist’s dummy, a passive vessel with drapery simply arranged across her surface. The body, writes Baudrillard, ‘particularly the female body, and, most particularly, the body of that absolute model, the fashion mannequin – constitutes itself as an object that is the equivalent to the other sexless and functional objects purveyed in advertising’. Does that victimize women? Debatable, particularly as the models themselves are complicit in their presentation. ‘Attitude’ is the notion lots of designers speak about today, designers like Demna Gvasalia of Vetements and Balenciaga. And where he leads, many follow. And that bring us, inevitably, to the idea of cool, which preoccupies fashion even today.

Cool is about more than simply being ‘in fashion’. Especially today, when fashion is everywhere. It’s about being in the right fashion, with the right attitude. The attitude of detachment so familiar on sullen teenagers’ faces is the current fashion standard. Models are, perhaps, not merely blank canvasses – what Baudrillard dubs ‘the void we rush to fill with our own dreams and desires’ – but intentionally distant, and therefore desirable, in themselves. Superior.

That ties with the ennui of the female gaze. It feels passive, but it can, in fact, be perceived as active but disinterested, too cool for school. The fashion model is unmoved by the clothing on her back, by their expense or sumptuous texture, in the same way that her historical counterparts are unruffled by the magnificent splendour in which they are posed. Monarchs rule by divine right, not privilege. There’s a degree of superiority to the gaze of the female model that ties her straight back to the royal portraits of the past, so confident of her position that no further assertion is necessary. The sitter’s ennui is in direct contrast with the active gaze of the observer, her voyeur. But rather than objectifying the model, it could be argued that the tables are turned, the observer’s desire impotent, eternally unfulfilled. They are, after all, just looking at a model on a page: a model whose gaze they can’t even meet.

Of course, there’s a counterargument. Commercial magazines delight in engaging their viewers, employing lingering eye contact to pull the observer into the page, to the product. Increasingly, the gaze meeting yours will be that of a celebrity, attractively packaged, accessibly placed, possibly with a piano-toothed grin, inviting you in. But what is the product those celebrities – both female and male – are selling with their come-hither gazes? More than the clothing on their backs, they are frequently hawking themselves and their talent as the primary product. Celebrities use magazines to flog a film, a book or an album. They may sell some of the clothes on their backs, but that isn’t their primary aim. They have both ulterior and interior motives.

The fashion model, by contrast, is open and blatant about her aim to sell a garment, rather than herself. A bland, expressionless disinterest amid the luxury is, arguably, seductive in itself. It directs your gaze from the blank face to the richness of the clothes, to the product that can – perhaps – be obtained. It also inverts old adages and challenges conventions. Today, sex doesn’t sell, it seems. Ennui does.

Photographer’s assistant: Julian Kapadia.

Stylist’s assistants: Mélina Brossard, Victor Cordero and Claire Tang.

Hair stylist: Mark Hampton at Julian Watson Agency.

Hair stylist’s assistant: Jonathan Mason.

Make-up: Fara at Frank Reps.

Make-up assistant: Laila Hayani.

Nails: Gina Edwards.

Models: Iana Godnia at Heroes, Sunniva Vaatevik at Viva London, Isabella Ridolfi at Viva London, Ally Ertel at The Hive Management, Kinga Rajzak at Elite London.

Agent: Alexis at Art Partner.