A father and son discuss style, styling, and the looks of the season.

Interview by Andrew Pearmain

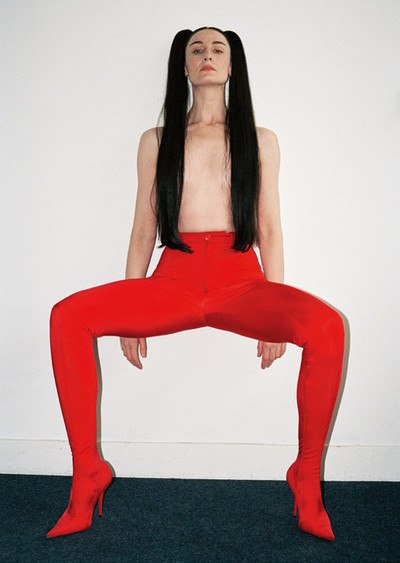

Photographs by Talia Chetrit

Styling by Max Pearmain

A father and son discuss style, styling, and the looks of the season.

Twice a year, stylists and editors the world over sit down, sift through images of all the collections presented in the shows six months earlier, and select the pieces they feel are going to define the upcoming season – in doing so, stamping their own sense of style on the contemporary fashion landscape. It’s a process that, as ever-more shows are staged for ever-more collections in ever-more places ever-more frequently, is becoming increasingly complex. So when System asked Max Pearmain if he’d like to do some of that sorting for us, it was as much a pretext for him to examine and question this most commonplace and traditional of stylist assignments – shooting the ‘looks of the season’.

As a contributing editor (and ex-editor-in-chief) of men’s fashion title Arena HOMME+, in-demand stylist and co-designer, with Anthony Symonds, of art-fashion label Symonds Pearmain, Max has long had a wide-ranging vision of what modern clothing can and should be, as well as the skills to manage fashion’s fine line between art and commerce, aesthetics and revenue, editorial and advertising. Which sounded like a good place to start a discussion. So we asked Max’s father, Andrew Pearmain – author, academic, political commentator and one-time punk poet – to have a word with his son. The resulting conversation around Max’s kitchen table takes in sartorial tribes, generational difference, and just what it is that Max does with his time. While providing the perfect weft to the weave of this season’s musts, as worn by Erin O’Connor and shot by photographer Talia Chetrit.

‘I’m interested in the connection between fashion and reality; by that I mean, giving off one signal, but hinting at another.’

Andrew Pearmain: I’d like to start by talking about dress sense, and where it comes from. Mine very much came from the streets of south Leeds in the 1960s, growing up and gradually coming out of absolute austerity where we had nothing, to suddenly being able to buy stuff, including clothes that said something about ourselves. For me, it was very much in a mod context, bringing together the spirit of working-class dandyism, European fashion styling, and something in there too about Jamaican rude boys. It gave ordinary working-class kids a sense of style if they were able to pick it up. Where would you say your own dress sense comes from?

Max Pearmain: I’m kind of envious of yours, because I didn’t have an obvious one around me. Growing up in Norwich, there weren’t distinct groups of people, but one thing I did have was a very strong fashion upbringing in the shop I worked in, Philip Browne, and watching people interact over clothing. It got me to the core of what I’m interested in, which is the connection between fashion and reality. By that I mean giving off one signal, but meaning another. I quite like the idea of camouflage, not in the literal sense, but the codes that come with being a man, what you can and can’t wear, but also what you can hint at. It’s sending out clues for someone who might feel the same way as you, that’s how I see dress sense. There’s also an issue of practicality. I like the utilitarianism of sportswear, but also the maleness of it…

The most interesting thing is that there are 30 years between us, two people forming and developing 30 years apart. I was talking all about class, and the context for my dress sense was a definite class location in a fairly fixed society. You’re talking about individual personal identity that you take on and develop. That’s basically how things changed over that 30-year period. There’s still stuff to play with in both contexts, so you talk about playing with masculinity, and so were we, playing with what being working class and male was all about, in a certain dandy or cissy version of that.

There is an issue of place, in that I was born in London, but we lived in Norwich. When I read The Face and other magazines, it was like an advert for this other place. It was always London oriented, and I used to go down to London from the age of 14. It was really exciting, without having anyone to share that with, to go and find things I’d read about. The physical journey was very important to me, actually going to London and going to find the shop where they sold these clothes I’d read about. Obviously, I couldn’t afford most of what I saw, but I was lucky to have that desire. I didn’t see that in other people at school, and it gives you a strong kind of motivation.

It was also available to you, and I do feel a certain sense of pride in making it available to you. You were making the journey back that we’d made the other way, out of London. But by then it was more available. My generation had to create our own dress sense, whereas for you, it was almost off the peg, you could go and choose. I’m not decrying that…

To be honest, I would rather have come from where you came from, because I think I would have enjoyed having those limits. The issue today is the total lack of limits.

The interesting thing historically is that we had literally nothing. I didn’t have my own pair of shoes until I was five and went to school; prior to that I wore hand-me-downs. My own first personal item of clothing was a pair of Levi’s that I bought with my paper-round money when I was about 13. So we had a much more limited but clearer sense of what was available, and we obviously valued it. We weren’t spoiled for choice.

I definitely had an inherited sense of value from you and Mum, and I enjoyed having the desire and ambition to work towards getting that stuff. I loved working in that shop, and you could see how prized the stuff was, the Helmut Lang stuff and whatnot… We didn’t have the Internet then really, no one had smartphones, so the shop was just this little fuzzy bubble you could go to. To be honest, I spent a lot of time just staring at the people who’d come into the shop, and editing stuff in my head because there wasn’t a lot to do, so I was able to work out why I found something interesting. I was also incredibly impressionable; I started there when I was 14. I was in awe of certain people and how they dressed. I wore ridiculous things, for older people and in wrong sizes. It didn’t look right on me, but I wanted to try it all out, like white Patrick Cox loafers with jeans with massive turn-ups that I bought in a sale because they looked like something I’d seen in a Face editorial.

It was as if you were playing a role, but that’s what fashion and being a teenager are all about. There’s also something in there about the relationship between the provincial and the capital.

Yes, and I actually valued the fact that we lived outside London. I’m always bemused by people who’ve only ever lived in London. And Norwich did have fashion; Philip took risks with what he stocked: Helmut Lang, Alexander McQueen, Vivienne Westwood. There was a slight underdog feel to that, these exotic things in that place. But my dress sense relates to all that – what it comes down to is, I’ll show you this, but it might be something else, and if it’s something else, do you get it? Do you understand what this means? Or what that means? And if you do understand, does it affect you, and if so how? It’s a dialogue, isn’t it?

‘I wore ridiculous things, for older people, like white Patrick Cox loafers with massive turn-ups. It didn’t look right on me, but I wanted to try it all out.’

I don’t want to bring you down to earth too much, but we were always aware that the clientele was a certain type – blokes with quite a lot of ready cash, footballers…

There were guys who worked on the oil rigs at Great Yarmouth who’d come in to buy their clothes at Philip Browne. And I totally loved that idea, that these guys from Yarmouth were wearing Walter Van Beirendonck, and, you know, paying in cash. There’s aggression in those undercurrents of menswear, like football casuals; you’ve got to be ready to fight if you’re going to dress up extravagantly. Not that I ever did… but it’s a Bowie-ism.

How does the fashion industry work? Where do ideas, different styles come from? What gets chosen above something else as the look for the season?

It’s fairly democratic. In blunt terms, there’s talent and commerce, some people who know how to present an idea that’s both intriguing and commercially viable. That’s why fashion is so interesting, because it’s a collision between selling and seeing who can do it creatively; it’s art and commerce mixing. In the context of the here and now certain designers can do that, Phoebe Philo, for example, Raf Simons, Jonathan Anderson; people who can be incredibly personal with their output, but also have heavy commercial clout. They create something seductive and interesting. Alongside that, comes a huge parallel machine for production and marketing that will say, we need this handbag to sell in this region, for example. That can also become quite dangerous because the marketing starts to dominate the creative, so that balance needs to be one that works. Partnerships really matter between the business leader and the designer, as does the amount of freedom the latter is given. For example, Pierre Bergé and Yves Saint Laurent were lovers and business partners and worked together to create space to grow both creatively and commercially. Demna Gvasalia at Vetements and his brother, Guram, who controls the business side would be another, contemporary example. The fascination is in the dance between business and creation.

Where does the money come from and where does it go to?

Money generally comes from perfume and handbags, accessories. It’s the bluntness of duty-free product essentially, but you need the seduction of the fashion catwalk collection to support the accessibility of the perfume and handbags.

Which explains the Symonds-Pearmain ‘Iron Lady’ perfume…

Yes, but it’s what we love about it, too, the strange bluntness. Yes, it’s about shipping perfume, but you’re also presenting this beautiful narrative in front of it.

So the perfume is a kind of tax that enables you to do what you really want to do. Where does all the money go? I was always aware as you were working your way up as an intern, and then even as an editor of a magazine, that it certainly wasn’t going to you! But there was lots of it sloshing around. The perfume sustains the creativity, but there must be an element of profit that somebody extracts…

People at a certain level of fashion earn a lot of money, whether that’s the the photographers, the stylists, the art directors, and obviously the designers themselves. Just like in the majority of organizations, that money generally goes to the people who are deemed the most qualified. Well, in most cases anyway! [Laughs]

‘There’s aggression in the undercurrents of menswear, like football casuals; you’ve got to be ready to fight if you’re dressing up extravagantly.’

Antonio Gramsci wrote, ‘The display of luxury is not fashion; great fashion comes from industrial development.’ Great industrial economies create a fashion industry, like the French and the English in the 19th and early 20th centuries…

That’s also because fashion is celebratory, the cherry on top of successful societies, you need something to wear to the dance, don’t you? It comes with the development of taste. In relation to that idea of taste and the consumption of taste comes one of my favourite quotes. Cindy Sherman was talking about a set of self-portraits from early in her career, and when asked about them her explanation was, ‘I just thought maybe I’d make some really disturbing pictures that people wouldn’t want to hang on their walls.’ I love that because it’s so problematic. Imagine Cindy Sherman actually producing something that people wouldn’t hang; it wouldn’t be possible now – she’s Cindy Sherman the successful and established artist, it would get displayed regardless. So the perception of your content is dependant on your status, and fashion is very status driven.

Even so, I think she was able to say that having already established herself on the top of a thriving industrial economy, such as America still was. I want to ask you about a sense of place, which I very definitively have, but you travel the world at a certain cosmopolitan level. I’m often struck when you say you’ve been in Paris, which is such a special place, but it feels like you could have been anywhere. Do you have a sense of where you are at any particular time, and does that in any way influence your fashion?

My sensibility is wholly English, and I really notice that in other countries, especially America. English sensibility and style are great, because it’s about saying one thing and meaning another. Appropriation is a very English thing. There’s a literalism in America, and they’re confused by that aspect of Englishness at times

The way we take bits and pieces of other stuff…

That’s why I like styling, because it’s about amalgamating several messages and creating a new one. You’ve got a pallet of colour to work with, and with that you can mix, and play and reinterpret.

On the one hand, that requires a degree of confidence in yourself and your own culture; not to have to retreat into it but be able to mix it all up and stick other stuff on top. On the other hand, it might also indicate a certain lack of self-awareness that you’re disguising and covering up through appropriation from other cultures. There is a sense about Englishness, that it’s both empty and over-full.

That’s multiculturalism versus provincialism.

Yes, and that’s what Brexit is all about, big city versus small town, whether you are closed off from the world or open to it.

For me, Englishness has always been about being open to the world, then making it English. It’s humour, it’s camp, playing with roles and character. Kenneth Williams and Carry On films, nudge nudge, wink wink. America in contrast is more literal, and we’re often suspicious of that…

We’re now being told we shouldn’t take Donald Trump literally; maybe he’s best understood as a misplaced Englishman! The last question I want to consider is how do we restore ‘cool’, by which I mean the central guiding theme of modernism and modernity, with all its components of restraint, simplicity, sparseness? The thought that gave rise to this question is: looking at so many fashion shoots, including some of the stuff you’ve been involved in, you get somebody young and beautiful and you could dress them in anything and they’re going to look interesting. Leafing through a fashion magazine, I’m just looking at young and beautiful people who’ve just had stuff thrown on them. There’s no sense of restraint, of less is more…

There are several aspects of this shoot I’ve done for System that are all about that kind of restraint. We shot ‘looks of the season’, so we worked with specific looks that I deemed in my head a definition of catwalk fashion at this moment in time, and it’s much more of a literal approach than I’m used to, taking quite specific things from the catwalks and putting them together very disparately on a model, who happened to be Erin O’Connor. She represented for me fashion as I was growing up. And Talia Chetrit, the photographer, is primarily an artist, and she was also interested in Erin’s heritage of working with very big fashion photographers. When I look through a magazine, I’m looking for some kind of quality control by people I know and understand. It’s a bit like reading music for a musician.

You’re a professional…

Yes, I look for a way of handling the material within frames of reference. For this shoot, I tried to let go a bit; we dressed Erin in a way that was wholly about the product, literally pieces of the season, we gave her these hair extensions. She’s a bit older, very beautiful. There were oddities to this shoot that made it interesting for me. I’m also beginning to feel more confident; I have the beginning of a context and a body of work that I can start playing with, at least in my mind.

Like a personal heritage, growing up and into yourself…

Yes, like a writer, in your case. It also links to the development of one’s own taste, confidence in it.

‘My idea of cool was Miles Davis. He was utterly confident in his choices to the point of not choosing something – like the use of silence in his music.’

Let me take you back a bit, because what you’re actually talking about is postmodernism. That’s another difference between you and me because I’m very definitely a modernist. Your generation feels able to pick and choose and throw things and see what sticks, but I feel profoundly uncomfortable with that. I have to pare things back and make conscious choices. But what I think you’re also saying is that in a professional sense you do make conscious choices, but just from a broader range than I was used to.

Of course, you have to. I would like to think I treat good product that already exists with respect, then produce my own work, which can bounce off it, but not imitate it. Imitation is dangerous, but it’s so close to adaptation. It’s a very delicate dance within a space that’s getting smaller and smaller.

And that’s the problem with postmodernism, that it just exhausts itself and everything else.

There’s just so much out there, you have to make intelligent choices, and push yourself to find them.

And at the end of the day it’s all about the process of choice…

Sure. The role of the stylist is all about editing, and I did that to the extreme on this shoot, editing it down, but also weirdly just letting go and not putting barriers between the looks, letting the fashion be literally ‘the fashion’. If that’s successful… well, I’m not even sure, but I was happy to set myself that task, set that problem up and see what it looked like made real.

So you’re just being a bit more relaxed about things. What we’re also getting at is the central myth of postmodernism, in that it looked like it was random and actually it wasn’t; there were choices being made. It made it look like everything was on an equal plane, an amalgamation of everything else, all of equal value and not discriminating…

I like the elitism of fashion – for me, fashion is a way of endorsing what you find important. It’s a lot to do with not trying to explain something away, letting something be the language you’re speaking in, even if it’s a dialogue that a limited audience understands.

So that’s what’s ‘cool’ — being confident in your own choices. My absolute ideal of cool was Miles Davis, and that’s what he was, utterly confident in his own choices, to the point of not choosing something, because he was famous for the use of silence in his music.

That’s a fundamental principle of good styling, which even effects how you act on set and what people expect of you. But I’ve seen how David Sims photographs, and he can be walking away from an image as he takes it. For me, that’s real talent, not constantly looking to impose oneself on the situation. He wants to remove himself at times. It’s really important to keep the silences in.