Legendary stylist, editor and so much more, Polly Mellen, on a life less ordinary.

By Jonathan Wingfield

Curated by Dennis Freedman

Portrait by Steven Klein

Legendary stylist, editor and so much more, Polly Mellen, on a life less ordinary.

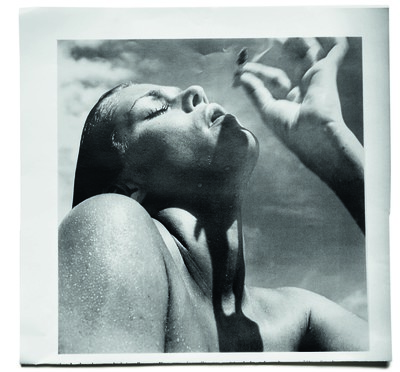

Polly Mellen is a legend. For over 50 years, she worked with some of the world’s greatest photographers to create images that have marked fashion history forever. There was the painterly yet scandalous bathhouse shoot with Deborah Turbeville for Vogue. And the daringly lusty 1975 shoot with Helmut Newton, cheekily entitled ‘The Story of Ohhh…’. Not forgetting the work with Irving Penn, Guy Bourdin, David Bailey, and Saul Leiter. And later on, with Herb Ritts, Steven Meisel, Mario Testino, and Steven Klein. Through it all, from the very beginning of her career as a stylist and editor up to the shoots in the early new millennium, there was Richard Avedon. Their professional partnership helped shape the vision of Harper’s Bazaar in the 1950s and Vogue in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, under the editorships of Carmel Snow, Diana Vreeland, Grace Mirabella and, briefly, Anna Wintour. Together, Avedon and Mellen redefined what women wore by changing how fashion envisaged their femininity and their new-found freedom.

Born Polly Allen in 1924 into a well-to-do family, Mellen led a cosmopolitan childhood, travelling widely. After serving as a nurse’s aide in a Virginia hospital during World War II, she moved to New York. It was there that she was introduced to Diana Vreeland – and grabbed her chance with the determined, go-getter joie de vivre she would later bring to fashion shoots and front rows around the world.

Dennis Freedman, who suggested we feature Polly Mellen in System, first met her in the mid-1990s, when he was the creative director of W, and she was typically encouraging (‘Young man, you are the one doing the best work right now,’ she told him). System and Dennis visited Mellen at her home in Connecticut on a snowy January afternoon, and discovered that, aged 92, she’s lost none of her enthusiastic, yet critical and avant-garde eye for fashion. It is a vision revealed in the portfolio of her work that Freedman curated for these pages. Selected from her personal archive of working documents, it is a treasury of what Mellen calls her life of wonderful ‘visual privilege’.

Jonathan Wingfield: I couldn’t help but notice all the pictures of your parents here. They seem like they were a very glamorous couple.

Polly Mellen: My mother loved colour, loved life, and was a very expressive woman. I mean, she weighed 250 pounds, and apart from the times she was in Paris or Rome or New York City, when she’d dress in black or navy, she only ever wore wonderful printed pyjamas. She practically lived in them. My father was extremely masculine, but would dress with great flair. He was borderline foppish; he loved beautiful clothes, many of which were made by a tailor at Saks Fifth Avenue called Wetzel. When they were in Cuba on the beach at the Havana Country Club, he’d wear a guayabera – a white shirt with embroidery all over – along with his terry-cloth, monogrammed white blazer, and slippers with green bows on them.

Were you dressed up as a child?

Mummy was always conscious of the way both she and her children dressed, so when, for example, we spent a summer in Paris or Cap d’Antibes or Juan les Pins, she’d put us in these little hats and braids, and we wore very short skirts. We were like ‘the little Allen family’: five children, a friend or two along for the ride, and a governess and tutor for us.

‘When I was quite young, somebody asked me what I wanted to do when I grew up and I just said, ‘I would like to work on a fashion magazine.’’

Did your sense of the avant-garde develop at an early age?

I think it started right there. I loved the sailors who sang to us at lunch; they wore their hats with the pompom on top and their middies, and I remember Mummy saying, ‘Oh, I’d love the girls to wear middies and hats like that, where can we get them?’ It was obviously a no-no because it was all official Navy uniform. Looking back, it was a wonderful upbringing; one of complete privilege.

Within your family and your circle of girlfriends from school, was it expected that you’d go out to work and have a career?

No. Besides my eldest sister Nancy, who was also a career girl, I was one of the few; it was just something I felt very strongly about wanting to do. When I was quite young, somebody asked me what I wanted to do when I grew up and I just said, ‘I would like to work on a fashion magazine.’ The fact that I ended up doing just that is down to a lot of luck, and meeting the right people who believed in me.

Prior to working in fashion, would you say that you had a rebellious spirit?

Yes. It probably comes from being the youngest of four girls. My sister, Patty, was 13 months older than me, and when children are that close in age you always get dressed alike. So I think I wanted to be noticed, wanted to be heard. I didn’t just want to be Patty’s sister; I wanted to be Polly. Thinking about it now, that probably brought out both some rebelliousness and some inferiority complex in me. To be honest though, I was a very good girl and a nice, sweet-natured person… at least, until I was 21.

What happened then?

I was a virgin until I was 21, but then I met a married man in New York City; he was 13 years older than me and the most attractive and exciting man who I had ever met. He awakened me to so much of life: he taught me to be brave and to let go and to embrace abandon and understand that there is nothing wrong or shameful in living the life you choose, even though he was married with four children. I fell deeply in love with him, which was very upsetting for my family.

Nice sweet Polly had been corrupted!

Mummy was concerned that my contemporaries would never satisfy me, because this was a pretty devastating man, hard to compete with. I mean, it was not a good thing for everyone, yet it was obviously a great thing for me, and we continued it for 15 years. It taught me the sexual side of life. When I later did ‘The Story of Ohhh…’ shoot in Saint-Tropez with Helmut Newton, Helmut would listen to my experiences from that time, and the pictures developed from deep emotions and feelings that I believed in, because I’d actually lived them.

The picture of the female model in that suggestive, almost masculine pose.

Yes, that was Lisa Taylor with the male model Peter Keating. In the pictures, you don’t know if they’ve made love, if they are about to make love, if they are getting dressed or undressed. Her posture also came from my experiences as a child in Antigua: there was a wonderful West Indian lady who’d sell eggplants in the market place, and she’d sit like that, which I guess could be construed as quite sexual, quite masculine, but she had an extraordinary dignity. It made me realize that my personal experiences could be transferred into picture-taking, in order to create powerful stories.

Before we move on to those other stories, I’d love you to paint a picture of post-war New York City?

I moved to the city in 1949. I was totally naive but very excited by what New York had to offer; it was so different from the protective WASP-ish environment in which I’d grown up. I’d gone to private schools in Connecticut all my childhood, but had a real appetite for experiencing other facets of life. I became heavily involved in things like the ballet and the opera, but was just as fascinated by the New York street, with things like the circus and the flea market, and the whole 42nd Street scene.

‘I was terrified of meeting Diana Vreeland; she was sitting there with lacquered hair, the snood and the bow, the grey turtleneck sweater, and her medals.’

Where were you living?

I lived in a boarding house for young ladies that was at 151 East 61st Street, and was run by a Bermudian lady called Mrs. Outerbridge Horsey. I was working as a salesgirl on the fifth floor of Lord & Taylor, which is still there today, but it’s not so interesting now.

What was your first experience working on a magazine?

Well, I progressed quickly from Lord & Taylor. I became head of the college shop – that was the closest I ever got to attending college – and then I went into window display back at Lord & Taylor, then at Saks Fifth Avenue, which was miserable. After that, I went to Mademoiselle magazine as a fashion editor.

What did being a fashion editor entail at the time?

For me, it meant going to the big salons and picking out hats for the stories that the other editors were shooting.

Was this all based in New York or were you travelling?

No, I didn’t go to places like Paris until I got the job at Bazaar.

Diana Vreeland was already at Harper’s Bazaar at that time, right?

Yes, and she already had a reputation for being this wonderful and eccentric woman, full of freshness. Her background was European and she had a sophistication that was more leftfield than Vogue, which was preoccupied with elegance, and had become a little repetitious. Bazaar had both Mrs. Vreeland – who was driven by finding new faces, new ideas – and, of course, Alexey Brodovitch, the art director with the most extraordinary eye.

What do you think made Diana Vreeland want to hire you?

She hired me because a couple of women who she respected had suggested she meet me. I was frightened to death at the prospect of meeting her, but I went in and there she was, sitting there with her hair lacquered, the snood and the bow, and the grey turtleneck sweater and her medals. She got up and shut the door behind me; I was so incredibly nervous, but we immediately got talking and just hit it off, and it was wonderful. I soon realized what a normal and fascinating person she was. She was also smart enough to sense how nervous I was, so immediately put me at ease so I’d share what my interests and passions were. She was always so hungry for information, and I guess she saw me as a new source. After that meeting, I had to see Mrs. Snow, who was the boss.

Because Diana Vreeland was ‘only’ the fashion director of Bazaar, right? Carmel Snow was the editor-in-chief.

That’s right. Once I was hired, there was no guarantee that I was going to stay. I had to do this shoot called ‘The Day Farers’, with all these horrible-looking clothes which I ended up turning inside out, just to give them some life, something new. Mrs. Vreeland went in to see Carmel Snow who said to her, ‘We can’t afford this young woman, Diana. We’re shooting “The Day Farers” for the fourth time. She’s out!’ But Mrs Vreeland said, ‘No, please, let me take her under my wing, let me work with her, it’s going to work out, Carmel.’ And it did. And here I am! It was all or nothing with Mrs. Vreeland; when she had a conviction, she never left your side.

Can you remember Richard Avedon being around at that time?

Dick [Avedon] was just starting there, too, but the big Bazaar photographer at the time was Louise Dahl-Wolfe– and Dick was definitely a threat to her. Believe me, you didn’t want to experience the ire of Louise Dahl-Wolfe! Carmel Snow wanted Dick for the magazine, so she snuck him over to Paris to shoot half of the collections, while Louise would shoot the other half.

What was your first shoot with Avedon?

Diana called him in and said, ‘I want you to shoot a portrait of a promising young actress called Audrey Hepburn, and I want you to work with Polly Allen.’ Dick must have already seen me at a show or something because he immediately said, ‘Diana, I can’t work with her, she is too noisy. I’ll get bad vibes from her.’

‘Diana called Avedon and said, ‘I want you to shoot a portrait of a promising young actress called Audrey Hepburn, and I want you to work with Polly.’’

What did he mean by that?

Well, he had a point! I keep nothing inside; I’ve always released my feelings. But Diana said, ‘Please, Dick, have her come and let her shoot with you.’ I will never forget it: it was at his studio above Longchamps on Madison Avenue.

How old was Audrey Hepburn?

She was just starting out, and she was adorable. She wore this yellow and white dress and when she got on set, she had no waist – 16 inches, like Scarlett O’Hara – which I wanted to exaggerate. I remember turning to Dick and saying, ‘I would like to do something, Mr. Avedon.’ He said, ‘OK, OK, go do something.’ I crunched up all this paper and put it under the skirt, which made it look really enormous and effective, and I remember Dick saying, ‘That’s great, Polly!’ He took the pictures and I didn’t utter a single word. Just before the shoot was over, Dick said, ‘Why were you so quiet, Polly? I like to have some noise on set.’ And from that moment on, I never was quiet.

How would you define your contribution to those Avedon shoots?

Well, I don’t know if other editors were ever like this, but I felt I really participated in the shoot, no matter who I was working with; I was always right behind the photographer – not in the way, just behind him, in the line of the camera – so I could see what he saw. And if I could see what he was seeing, then I could communicate that back to Lauren Hutton or Sophia Loren or Fred Astaire, or whoever was in front of the camera.

Did communicating with the models and portrait sitters come naturally to you?

I always considered that to be a main responsibility, to woo the model into being shot. One of the early shoots with Dick was with Nureyev. Gosh, wonderful, incredible! When he jumped, his physique was so unbelievably statuesque, like stone. But between frames, whenever I went over to discuss the next shot with him, he’d turn and have his back to me. He was rubbing himself so he would be ‘full’ for the next picture. And then he’d turn around to me! I loved it; I mean, I was sitting right there!

How was Mrs. Vreeland about all this? Was she goading you to get the shots?

Goading me and how! She loved sexy guys, all those photographers like Patrick Lichfield. Everything about Mrs. Vreeland centred on pushing you to do the best, the newest. She brought me to Vogue in the mid-1960s, and my first assignment was a whole new level: five weeks shooting in Japan with Dick Avedon and Veruschka.

Five weeks? The budget must have been eye-watering.

I’m proud to say it was the most expensive shoot Condé Nast ever did. They never did one like it again! I had 16 trunks of clothes, no assistant, and I basically became Japanese for a month.

Shoots these days barely last a day.

This was exceptional, and we knew it. Believe me, all the other editors, like Babs Simpson, wanted that shoot, but this new woman who’d come from Harper’s Bazaar got it – it wasn’t fair. I said to Mrs. Vreeland: ‘I feel an animosity towards me from the other editors, and I don’t feel like I’ve really made any friends.’ She just said, ‘Who needs friends, Polly? Go about your business and concentrate on this extraordinary trip to Japan. Oh, and by the way, as part of your research, read a book called the Tales of Genji.’ It turns out it’s the dirtiest book you’ll ever read. Mrs. Vreeland hadn’t actually read it herself; she just got me to fetch a copy, read it, dog-ear the pages of the best bits, and pass it on to her.

What do you remember most about the trip to Japan?

So many vivid memories. One time, it was about five in the morning in Hokkaido, the uppermost main island in Japan, and we were on a hill overlooking the sea. We were getting ready to take a picture, which was taking forever, when I heard this humming music in the distance. All of a sudden, these very sturdy, dark-skinned women appeared through the mist; they were all wrapped in white fabric, like gauze, which they undid, dropped their tops, and then greased their bodies all over, before covering themselves up again in their white gauze. And then, one by one, they all dived into the water. Turns out they were pearl divers. It was so poetic, so unbelievably beautiful.

You’d mentioned that your upbringing was one of privilege, but your adult life feels equally extraordinary…

I think of my life as one of visual privilege. It continues to affect me today when I think about all these wonderful visual moments that I experienced over the years. There was one ugly moment though, in Japan. Akira Kurosawa was having his portrait taken and Dick wouldn’t let me be there. I’d been so excited to be on that shoot, but he just flat-out refused. I was hurt, sad, furious – everything!

‘My first assignment was a whole new level: five weeks in Japan with Avedon and Veruschka. It was the most expensive shoot Condé Nast ever did!’

Talking of being hurt and furious. Your work is now celebrated as having been pretty avant-garde and challenging for its time, but were any of your shoots rejected at the time, killed by the editor?

That was something you just had to deal with. Sometimes I managed to get some of the pictures in and sometimes I didn’t. But, you know, the boss is the boss. And I respected that. And she was quick to say, ‘I am the boss, I am the editor-in-chief, it’s my magazine, and I want you to re-do it Polly.’

What would happen then?

Dick always refused to reshoot! We’d move on to a new photographer and a whole new story.

How often did that happen?

Only a couple of times, I think. Once was when we’d been in Paris shooting the collections: Dick photographed Veruschka and the make-up artist was Serge Lutens. The clothes were very beautiful and she was amazing, but they became very surreal and strange pictures. Serge made Veruschka chalky white, and you felt like you were in the fog, like in a movie. It was very interesting, but it had nothing to do with Vogue magazine. I just instinctively felt, ‘This isn’t going to fly.’ True enough, they said, ‘Absolutely not, we’re not publishing anything like this in Vogue.’

Did you see beauty in it?

It’s funny what I see: I can see beauty; I can see ugliness; I can see a lot of different things. At some sittings, it almost felt like a film and it was very easy to get completely wrapped up in it. I did a bathing-suit shoot with Deborah Turbeville that became like this.

The incredible shoot in the bathhouse. That was done in New York, right?

Yes. It was for Vogue. It was great fun and when all those pictures came in, I showed them to Grace [Mirabella], who was the editor-in-chief, and Alex [Alexander Liberman, Vogue art director]. You could immediately tell that Alex was very, very interested, and that Grace was horrified. I knew from her look that it was going to get killed, and that angered me so much, because she was wrong on a lot of levels. Alex just put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘Polly, why don’t you go for a walk?’ When I came back, he said, ‘Polly, we’re going to publish this shoot, it is amazing. But we will call it a feature; it will not be in the fashion pages, and that way I can get it published the way I want to.’ Grace knew that the pictures were special, but her point of view, which I obviously respected, was that they don’t belong in thie magazine. It was said that the pictures resembled a prison camp, like Belsen, which made me feel sick. But all the pictures finally got published and, my god, they are still being published to this day.

Were you ever accused of vulgarity?

Once, when I was at Harper’s Bazaar. I did a shoot with Suzy Parker wearing a raincoat with black pumps and no stockings, which was very shocking for the time. She’s walking with one hand in her pocket; I think I’d been influenced by Bogart and Bacall in To Have and Have Not. The pictures came in and I got a call from my boss, Nancy White. She put the picture with the hand in the pocket on her desk and said, ‘What’s going on here, Polly?’ I was – and still am – very naive to a degree, and I just said, ‘What are you trying to say Nancy?’ And she said, ‘We don’t publish a picture that implies that something is going on with her hand in her pocket.’ I didn’t know what the hell she was talking about! So I picked up the phone and called Dick and he said, ‘Masturbation, Polly!’ I was so shocked; I said, ‘I never thought of that, I don’t have a dirty mind. Did you think of that?’ And Dick just said, ‘Of course! And Nancy White clearly did, too!’

It seems that fashion photography’s most iconic images are often born out of mistakes, happy accidents, the unplanned. I’m curious to know your thoughts on this.

I’d say the planning, if that’s the correct term, is my responsibility, and the photographer’s responsibility to woo the model. And without that there is no chemistry; there is no excitement; there is no possibility of the unplanned moments you refer to. The model is dressed – she’s in Dior, she’s in Saint Laurent, it doesn’t matter – she feels beautiful, she feels wanted, let’s go. So once you’re in that moment, the mistakes and the accidents can happen. And if there’s a mistake – I left a body pin in the dress – so what? Leave it in, don’t take it out! So a bra strap is showing, let it show! It’s exciting. I remember shooting in Saint-Tropez with Helmut and I put a black bra underneath the model’s naive little gauze top, and Helmut saying, ‘Brilliant! Black bra! Brilliant, Polly!’ Ultimately, imperfection is a good thing if it works, but it is up to you to create the tension and the chemistry in which it can work. I was always very lucky. With Avedon, Penn, Newton and later on, Steven Meisel and Steven Klein, the magic was there.

‘I asked Nastassja Kinski if she wanted to do a picture with a snake. She said, ‘Yes, but I’d like it to be a really big snake, and I’d rather be naked.’’

Can you give me a specific example of the wooing, the creating of tension and chemistry?

The snake picture with Nastassja Kinski is the obvious example. I was in LA with Dick, taking what I thought were pretty mediocre fashion pictures with her. I’d seen Nastassja before and watched her movies, and I felt that here was a really strange, beautiful, young woman, and I wanted to express that in the pictures. I wasn’t thinking about the clothes or the ambiance, I was simply thinking, ‘What do I want to have going on with Nastassja Kinski in the shot?’ So I asked her if she had any favourite hobbies or anything she liked that kind of turned her on. And she said, ‘Oh yes, I like snakes.’ I asked her if she wanted to do a picture with one, and she said, ‘Yes, but I’d like it to be a really big, beautiful snake, and I would rather be naked.’ Now, I don’t know if you’ve ever held a snake… it is so erotic, you cannot imagine, it’s like holding your lover’s penis, it really is. And so Nastassja lay down and the handler passed her the snake. And the magic happened: it started to wind around her body and I just couldn’t believe it. Oh my god! When it got to her ear, it kissed it with its tongue, and Dick caught it on camera. One single frame, and the sitting was over. I was crying, literally. It was such an emotional moment, that came from a perfectly banal shoot. Not only did I let go, but Nastassja let go, the snake let go, Dick let go. Just one of the magical things that I was lucky enough to witness.

Besides Avedon, you also worked with Irving Penn, whose approach was known to be totally different. Tell me about creating chemistry in his particular environment?

Penn’s studio was all about calm and silence. There was no music, no smoking, no nothing allowed. But I remember one instance of breaking that with Leslie Winer, a young model who people said was a drug addict. She arrived one day and asked if she could bring a friend and I said, ‘Yes, but on the condition that you both remain quiet and don’t smoke.’ Well, of course, they were both chain-smokers; her boyfriend sat at a little dressing table sketching, and they’d go off the bathroom to shoot up or whatever. She’d come out, go down to the studio, and then completely woo Penn because she was high and very expressive – it’s always stuck in mind because that wasn’t Penn’s style at all. When the shoot was over, the boy Leslie had with her tossed all his sketches in the wastebasket, and they left. Turns out he was Jean-Michel Basquiat!

This was in New York, right?

No, this was in Paris in the early 1980s. Oh, he was so adorable, just such a wonderful face; they were giggling and so high and making out, and he was under her skirt. These are the sort of things that you just deal with on set, and I sort of ate it all up because I felt that there was a spirit that happens in the dressing room, and an energy that you have to ignite. As I mentioned before, you need to make the model feel beautiful and interesting; you have to turn them on, because you’re about to send them downstairs in front of Irving Penn’s camera.

You obviously witnessed many changes in the magazine and fashion industries over the years you were working. How did you experience this evolution? And how did you continue to remain clued-up, curious, enthusiastic?

When I left Vogue the second time, it was because Anna Wintour brought in Grace Coddington. We were both very outspoken about the fact that it wasn’t working having two creative directors, so I moved on to Allure, which was a very difficult spot for me. I mean, in that environment, you learn mediocrity, and you hear about business being everything. But within a culture that’s led by the bottom line, I always felt that I had to exercise my curiosity even more. So I’d make a point of seeking out young talent, and going to the little shows they’d have in SoHo lofts. It was out of curiosity, but also that little thought in my mind that’s always saying, ‘How do you know this isn’t going to be the next thing?’ It might be good or it might not, but it’s the ‘might’ that you are there for.

‘I had to make Leslie Winer feel beautiful and turn her on, because I was about to send her downstairs in front of Irving Penn’s camera.’

Did it pay off? Did you get to see some significant designers early on in their career?

I remember one time that [fashion PR] Keisha Keeble called me and said, ‘You have to come and see this guy’s work’. His name was Stephen Sprouse. I walked in and he seemed completely high, but I was so stunned by the colour. The clothes were almost manly. I mean, there were leggings and a T-shirt and a man’s coat in fuchsia, but I’d always respond to something as striking as that. The point is, you’ve just got to go out and see it for yourself, and get behind a designer’s work if it’s something interesting.

What about in Europe?

I always went to see Martin Margiela, who was a total innovator, or those incredible Comme des Garçons shows; the ones that everyone talks about now, even though Anna Wintour never ever went along. The show that sticks in my mind was the one when Rei Kawakubo distorted the body by transforming these cute cotton gingham summer clothes with lumps of cotton. It was childlike, yet grown-up, and you’d be thinking, ‘It this fashion? Is this an art performance?’ I felt such an affinity with those kind of collections.

Do you see that sense of daring in fashion editors today?

Camilla Nickerson, who I admire, continues to be daring. But today there isn’t much work out there for minds like that, and how they see the world. I have great respect for Anna Wintour, but she likes ‘pretty’. And today she is so big that her magazine still sets the tone for so much else. I’m sorry, it doesn’t turn me on. Why would it?

What about today’s photographers?

Certain things interest me a lot. For example, I’d love to know who shoots today’s Yves Saint Laurent advertising.

It is Collier Schorr.

I think that work is fantastic. There’s a picture of two girls kissing: you are not aware of the clothes – you’re not meant to be aware of them – but you can’t help stopping and thinking about Yves Saint Laurent. It’s not about any specific garment; it’s about the world that woman inhabits, and that’s a Saint Laurent world.

Do you miss the camaraderie, the sense of community that comes with fashion?

Goodness, no; I am a loner. I became that way over the years because I didn’t feel like I was meshing with what that working environment wanted.

Like a self-prescribed isolation.

Yes. I would be very genial on shoots, but at night I’d go back to the hotel, order room service and think about the following day. That was my constant responsibility: I’ve had all these privileges, now I’ve got to use them visually. I don’t mean with conceit, just with straightforward honesty. Does that make sense? Before you came here today, I wrote down some notes – as much for myself – about how I consider the way that I work, and the way I see the world, then as now. [She reads from a notebook] ‘Adjusting, keeping quiet and always moving on. The push and pull of making one’s voice heard, but always listening, because that’s the game, especially when you’re not the boss. And, finally, never being a pessimist. Optimism always prevails.’

That’s wonderful. Finally, are there moments today when you think, ‘I’d like to get out there and do a shoot’?

[Laughs] Well, I’m 92 now… but let’s just say I get teased by the idea every once in a while.