How Shiseido’s advertising changed the way Japan saw itself.

By Ruba Amu-Nimah

How Shiseido’s advertising changed the way Japan saw itself.

Ikuo Amano was appointed creative director at Shiseido in 1966, a year after graduating from Tokyo University of the Arts. By that time, the Japanese skincare and beauty company had grown from a single Western-style pharmacy in Ginza, Tokyo, opened in 1872, into a burgeoning multinational. Amano, working with photographers including Noriaki Yokosuka and Kiyosuke Kajihara, and models such as Sayoko Yamaguchi and the Lutz sisters, Adelle and Tina, opened up the company’s visuals to new influences by mixing the quiet poetry of their Japanese sensibility with the striking geometry and abstraction of contemporary Western visual culture. Combined with the profound changes in Japanese society being brought about by the country’s increasing economic power and a new cultural openness, Amano’s images helped revolutionize advertising in his homeland and build his company’s reputation abroad.

System asked Ruba Abu-Nimah, who until early 2017 was Shiseido’s creative director, to talk to her illustrious predecessor, Ikuo Amano. The pair met in Tokyo where they talked about his pioneering work, how a still-relevant visual identity was born, and what gives a local brand a global outlook.

Ruba Abu-Nimah: Let’s start at the beginning in the 1960s.

Ikuo Amano: I began working for Shiseido in 1966. I’m sorry, but I need to say a lot about the 1960s before I go into the 1970s, so this is going to be like a prologue, but bear with me. In the early 1960s, before this, Shiseido was doing mostly illustrations. Of course, we had cameras and we had photography, but we didn’t use those in advertising. We were mostly using illustrations by Ayao Yamana. But a Shiseido poster from 1966 was one of the very, very first posters that used photography for a campaign. For me, it was very shocking to see this poster when I first joined the company. No matter how many times you put them up, the posters would get stolen. That means people wanted or needed to see them. People who did not want or need any cosmetics wanted these posters. That’s how intriguing they were, and I think that it shows how much these kinds of visuals had an impact.

Beyond being a cosmetics advertisement, that poster represents a point of view, a paradigm shift in design and art direction, and almost a cultural revolution coming out of Shiseido. Did you feel, when you arrived, that you were about to witness something very new?

Yes, I did feel newness in that movement. In the world of illustrated campaigns, we did try to express beauty, but those illustrations didn’t show the strength or the power or the reality that photography does in these posters. For the poster in question, we worked with an art director called Eiko Ishioka. She brought out these very strong eyes that are really glaring at you. In this era, Japanese people were trying not to get sunburned, but at this point, we were trying to tell them, ‘Why don’t you make sure that the sun really loves you?’ After this poster came out in Japan, we had this kind of vacation phenomena, when everybody wanted to go into the sun to get a suntan. That was the kind of phenomenon this poster created. These very strong eyes, as if she’s looking straight at you, that was unique at that point; it was not the fashion. Not only in beauty – fashion campaigns did not really show this much bare skin on posters in Japan, so that was rare as well.

It was important in the history of Japan.

Exactly. You can see that this was a trigger, which led other companies to do these kinds of big, flashy campaigns as well. Not just on posters, but also in TV commercials, print ads, and newspaper ads. I think this moment in time – the 1960s and 1970s – was really a turning point, when companies started to focus more on advertising. Particularly as, at this time, we were seeing very strong economic growth.

‘Shiseido’s 1966 campaign was the first to use photography, not illustration. No matter how many times we put them up, the posters would get stolen.’

That’s the way I’ve been working in New York for 20 years. A creative director has to bring the best experts together. Then, if each one does their job properly, you get something magnificent. The industry has changed and doesn’t allow for that way of working anymore. Were those values Shiseido values? Or are they just Japanese?

I don’t think it is unique to Shiseido. I think we were probably one of the first to do it in the industry though. It became more general in society after the 1960s, when we had this international fair. In 1960, there was this World Design Conference. This word “design” was already used in Japan before 1960s, but it wasn’t used generally. Up until then, in the world of design, the actors, or maybe we should say artists, were trying to pursue expressing their individuality, and that was it. But once we had the international fair come to Japan, we started to try and find ways to collaborate. This wasn’t only limited to the graphic-design world. It was about a wider collaboration, with graphic designers collaborating with fashion designers, architects, industrial designers. Everyone started to think about collaboration, and I believe the trigger for that was this international fair in 1960.

Good art sells product, and when I look at this, I see art; I see marketing as secondary. What role did marketing play in your creative strategy?

This poster did sell a lot of the products. We had a lot of great sales for sun oil. We had this vacation phenomenon. This was also the first time that we had gone out to a specific location to do the photography. Before this poster, Shiseido’s posters and advertisements were always shot within studios and only showed the picture of a model from her breasts and upwards, so just the top of them. I believe these posters gave the advertising industry courage to bring their point of view out forward.

Do you think the industry still has courage?

It is decreasing. It’s 50 years since I joined Shiseido, and there have been many changes in those years. Cosmetic products, especially after 1980, shifted their role in society. Everyone started to focus on the quality of product, and the specifications of the products themselves. At that time, we also found that the advertisements became the same, even though they were produced by different companies. Now we see computers coming into the game and we see that photography can be retouched so many times, or entirely digitally composed. These advertisements are not lying, but they are retouched realities, and they now all look the same.

Myself, and others say the same thing today: we believe the beauty industry is now lying to the consumer. Advertising has become completely homogenous and dishonest. What’s your advice on bringing it back to an honest reality?

We need to cherish our heritage, while obviously at the same time, ensuring that we have a continuous evolution or revolution going on. Rome was not built in a day, but of course, Shiseido wasn’t either. We have our very rich heritage and have always cherished our history; we have always tried to keep it safe, and consider it an essential core of the brand. Yoshiharu Fukuhara, the head of the company, always says that there are certain important pillars to talk about when we talk about Shiseido. One is to make sure we use our history when we have a story to tell. Our research and development and our technology should also be developed throughout time, taking into account our heritage. We also need to make sure that the products have a humanity. All of this was in a book he made.

What year was this?

It was 1997, the 125th anniversary of Shiseido, and the book was distributed to all employees, with the brand’s values. Shiseido now has a 145-year history, and the corporate culture developed in that time is like a precious treasure. It provides a foundation; it’s like a whole museum for us. At that time, for advertisements, our team was growing as we had started to incorporate many professionals into one team. We now had an art director, a photographer, graphic designers, copywriters, producers, make-up artists, and stylists. We found ourselves working in these gigantic teams.

I’m very interested in the idea of this collective culture, and in collaboration. For example, the work that you did with photographer Noriaki Yokosuka. That seems really important; he photographed some of Shiseido’s most iconic images. I would love to hear about the process of working together.

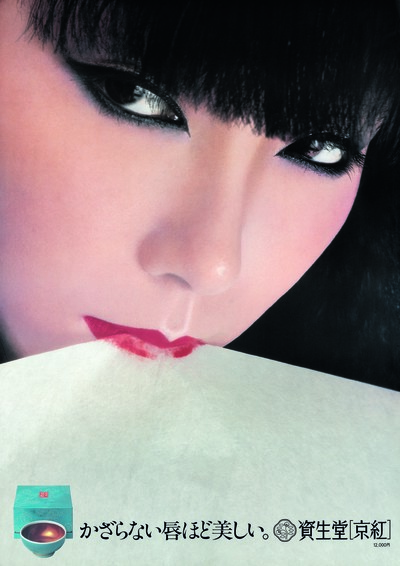

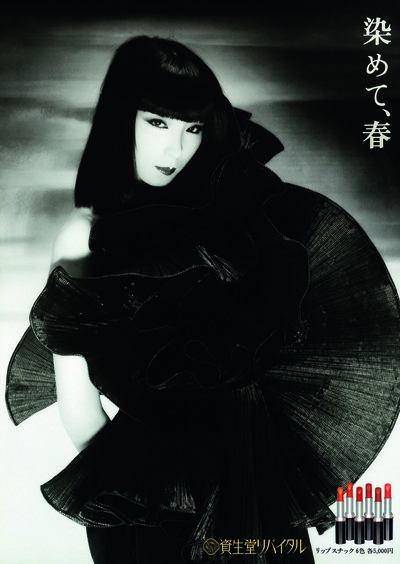

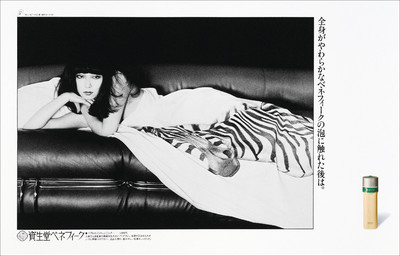

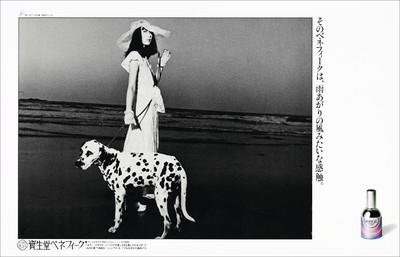

Firstly, I would like to talk about the history. In 1970s Japan, after experiencing very strong economic growth, we were in a different era. The population had grown, and we found ourselves – nearly the whole population – in the middle class. We also found that the consumers were starting to mature, and Japanese fashion designers were beginning to go global. They began debuting in Paris during fashion week. For the Japanese, it was a foreign world. We were even writing phonetically: the headlines on posters were ‘Pink Pop’, and ‘Beauty Cake Lip Art’. Because of this, at that time, we used half-Japanese, half-foreign models. Then one day Yokosuka came to me and said, ‘I know this model called Sayoko Yamaguchi, and we need to use her.’ Her hair was short and she was very white. She had this talent to express herself, and you could feel that the minute you met her. Before we used her for the Benefique campaigns, though, we did an advertisement with her that said, ‘Good morning, skin’. That was in 1972 and the first time we shot her for Shiseido. Nobody else knew her. This is an advertisement for night cream, and usually at this time, that kind of skin cream had advertisements showing the night, or the model right before she went to bed. This was different. This showed the morning after she applied the cream, and had slept. It showed how dewy your skin could be, matching it with the morning dew on the leaves in the image. That’s why Takeo Onoda, the copywriter, added ‘The skin that says “good morning”.’ The phrase ‘good morning’ was about the promise of a brand-new day.

They’re quite brilliant. It’s very conceptual.

We needed to have a different advertisement every month, so we were always photographing. We were not in a digital world like now; everything was analogue. We would take a picture and cut out all the text, and then place it on top of the images. We would ask the printers to work on it, but they wouldn’t give it back to us until the next day, so we had to wait and wait for things to be ready. So, I would go to the movies and to museums. I had abundant time to explore and to really look at things. Today, because we are working at such speed, and sitting in front of the computer for such a long time, we’re not able to really look at things, and explore. Around this time, everything started to appear in colour, so we took the opposite tack and did monochrome advertisements. We wanted consumers to use their own imagination, imagining what the colours could look like. You can also see that we photographed the models from a very wide angle because fashion had started to enter beauty advertising. In the 1960s, you would probably see a close-up of the face, but we shot the clothing, interiors and urban backgrounds.

‘Everything started to appear in colour, so we took the opposite tack and did monochrome advertising. We wanted consumers to use their imaginations.’

Was this unique to Shiseido or were other beauty brands doing that at the time?

Many other cosmetic companies started to do similar kinds of layouts, but we always tried to be unique, and try not to be affected by whatever the other companies were doing. When we did the monochrome advertisements, I was the art director and did the design as well. What was interesting at this time was that Junko Koshino, a Japanese fashion designer, was working with us as a stylist. She would bring her own clothes, ones she had designed, and her own accessories; the props would be her own. She would always come to the meetings with many, many – maybe sometimes even 10 – variations of what she wanted to dress Sayoko in. She was really determined and had strong wishes for each campaign. Usually you’d start out with a pre-planned situation and location, and after this has been defined, you would ask the stylist to come in, and you would direct her. But it was the other way around when Junko Koshino was with us – she would bring out all these great ideas. We would be inspired by her dresses – maybe even the itchiness – and the interesting things and ideas she would bring. We would then decide on the locations and how and where we would like to place the model.

How much of an impact did the casting, with Sayoko, have on the work you did?

When we were making these kinds of advertisements, we weren’t showing the model any pictures of what should be done or how she should be posing. Yokosuka, the photographer, really didn’t believe in that either. He would get all the inspiration on site; he was inspired by the moment. He would start working with Sayoko, who would then respond to the atmosphere, and who would pose in response, again inspiring a change in the atmosphere. Those two would work together, and bring out something very rare. I think you could say that having Sayoko brought out the artistry in both her and us. Having her with us was one of the big reasons we were able to continue this series for such a long time. The presence of Yokosuka was very essential as well.

It wasn’t only work for me. When I work with someone I try to establish a human relationship with that person, and then the work comes after. With Yokosuka, we ate together a lot; we drank together a lot. We did a lot of work together and so this kind of great relationship was something that was really essential for our work, too.

This set-up was very diverse for a Japanese company in 1971.

Maybe, but it wasn’t that intentional.

But it’s important. You’re talking about authenticity and brand values. How have they changed at Shiseido since the time you were creating all of this extraordinary work?

What has changed is not the values, but the point of view and our behaviour. What has not changed is the response to the aesthetics of beauty – how your heart moves when you see something beautiful – and the feeling that you want to really make something good, or do something good in your life, and in your company. We were talking about mass production and mass consumption in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Why was Japan able to become this country with the big, gigantic economy? It was because we were trying to make everything in a uniform way, so our education was uniform and the products that we manufactured were uniform. Without this uniformity, I don’t think we would have ever been able to reach the high-speed economic growth we saw in that era. We are now in a different era, in an era of greater diversity, in beauty and in general. Diversity is a word used often now, and it is far more important to position yourself in that context, and ask how advertisements should be now. What is the ideal advertisement today, and what is the ideal way of creating a product? I think the axis or the core of such thinking has changed.

‘Why was Japan able to become this country with a gigantic economy? Because we were trying to make everything in a uniform way. Diversity didn’t exist.’

You’re talking about uniformity in Japan, but that was happening at the same time as you were creating something specifically individual and nonconformist. Were you working against the grain? Or were you doing something in line with what was happening in Japan at the time?

Yes, I think I was in line. When I look back to that time, there was so much change. We had the Tokyo Olympics, all the new highways, the monorails running – everything. The whole environment had changed in an instant. With that, we saw a big leap in technology, and printers were able to print mass amounts. That enabled everyone to have the same thing, at the same time, and to reach different locations quickly, so advertisements became central. I had one more big project, working with Serge Lutens. I think around 1977. In America or Europe, it might have been very different, but in Japan, women had really started to go out into the society, and to work at the same level as men at that time. Cosmetic products before then were designed to be beautiful when displayed on the counter. The creams, the lipsticks would be big and beautiful, but at this time we started to think differently. We wanted everything to be light, slim and short – very easy to carry around. So we created a new brand, which cut out everything that was not essential. We called it Inoui and we created products that allowed women to have these cosmetics in their pockets, at their side, accessible at any time. I don’t think we have the Inoui line anymore. At the time we developed it, the mission for big brands was to make sure that they catered to masses and had great sales. Inoui was a little different. We weren’t asked to make a big contribution to the overall sales within the company. It was positioned so that having Inoui as a Shiseido brand would symbolize Shiseido’s position as a very fashionable, progressive brand. We knew Shiseido had its own culture, its own history, but it was like Shiseido was becoming a brand that had already fully bloomed and we needed other flowers on another branch to come through. Serge Lutens was the person who was able to bring that to us. Issey Miyake and our model, Sayoko, introduced Serge Lutens to the company president at the time, Mr. Ono. Mr. Fukuhara was working as an advisor at that point. These two top management people took the decision to bring Lutens on board. I had a wonderful opportunity to attend the meeting in which they made that decision, and was therefore given the chance to work with him. So we worked together with Serge Lutens on Inoui.

Shiseido has always been very outward looking. It’s been a very Japanese company, but at the same time, from the beginning, it has looked to the West and incorporated that into everything. How did that affect your work?

My understanding of the company was that it wasn’t trying to become Westernized at all; we thought of it as a hybrid. In 1872, when it was founded, the premise was to have Eastern culture as its mother, and to have Western, well, not culture, but the West as its father. We have a word in Japanese, wakonsosai, meaning the Japanese spirit or the Japanese thoughts aligned with Western skills and technology. I always thought of Shiseido as trying to pursue something as a combination between the East and West. I think of ranges like Inoui and Tactics as being representative of such a hybrid. For instance, Inoui was a combination of Japan and the US, and Tactics was, I think, more of a combination between Japan and the UK. Lutens mixed his own sensitivity with Eastern sensitivities, and this is what brought Mr. Fukuhara to say that he and Serge Lutens have very similar values. They had this kind of dialogue, which they discovered while working on Vogue, where they spoke to each other and agreed that they had some kind of affinity with one another. Also, they shared a birthday, March 14.

Emphasizing history helps to determine how a brand can maintain its authenticity, as well as move forward. What advice would you give people working in the beauty industry today?

In one small sentence, it would be this: yes, this era is digital, but humans are analogue. We are flesh. This applies to product development and advertising. This is an extreme example, but when I retired from Shiseido in 2001, it was the same time that we opened its Shiseido Parlour. It was a big events space, and I remember there was this giant screen, and it was showing visuals of Ito Jakuchu. He is a Japanese painter, and his work was shown digitally. When you look into the Edo period, the time at which Jakuchu painted, which was more than 100 years ago, they didn’t have the speed we have today, but they had speed in their bodies – physical speed. As an art form, that applies to cosmetics. We cannot forget that humans are analogue. Let’s keep the physicality of art in mind as we continue to work digitally.