Washington Post fashion critic (and Pulitzer Prize winner) Robin Givhan on the politics of appearance and the appearance of politics.

By Jonathan Wingfield

Photographs by Brigitte Lacombe

Washington Post fashion critic (and Pulitzer Prize winner) Robin Givhan on the politics of appearance and the appearance of politics.

In March this year, White House press secretary Sean Spicer attended a press conference wearing odd shoes, as if he’d fallen out of bed and panic-dressed. It wasn’t the first time that his clothing had become news. President Trump was reported to be extremely displeased that the ill-fitting suit Spicer wore to his first-ever press conference looked like he’d borrowed it for the day. Because, as Robin Givhan often notes, Trump clearly understands that how you present yourself in politics matters. She has been writing about this revealing mix of clothing and politics for many years, perhaps a natural gig when you’re the fashion correspondent for the Washington Post, the newspaper of record in the US capital.

In 2006, Givhan’s writing won her a Pulitzer Prize for what the jury described as ‘witty, closely observed essays that transform fashion criticism into cultural criticism’ (an alchemy much rarer than it should be). She sees fashion as far more than regular bouts of hysterical exhibitionism; it is also a lens through which society reflects and reveals itself. For her, dealing with the appearance of politics is an integral part of her larger role interpreting the politics of appearance. (Which she regularly does in beautiful prose.)

System recently sat down with Givhan in New York, and later on the phone from her home in Washington D.C., to discuss how a career that began reporting on techno ended up on fashion’s front row; the importance of the written word and its physical presence; and how a journalist’s first priority is her readers, always and forever.

Part One

‘I had no idea about fashion,

nothing, nada!

I liked clothes, but that was it.’

Jonathan Wingfield: You were born and raised in Detroit… which is now suddenly Hipsterville!

Robin Givhan: When I was growing up there, it was a standard Midwestern city that was a bit down on its heels, but still a pretty lovely place with extraordinary Albert Kahn and Frank Lloyd Wright architecture. But by the early 2000s it had spiralled into bankruptcy, post-industrial urban decay, and sadness. As it started to come out of that, Detroit became this very fertile city for entrepreneurs, artists, and people who want to kind of recreate themselves. And because it was really affordable, it became this burgeoning mecca for hipsters.

Why do you think people always romanticize the perceived grittiness of Detroit?

It’s never had the glamour of Chicago, but that grittiness gives it an authenticity that can be hard to come by in the States, as so many cities have become defined by their glass-and-steel towers. Detroit has very few genuine skyscrapers; its grand office towers have that post-WW2 limestone and marble look, and I’m convinced some of the romanticism comes with that.

‘My first job was on the entertainment section of the Detroit Free Press. I had my own beat about the city’s burgeoning techno and rave music scene.’

I’ve read that you were always top of the class throughout your academic years. Was there a history of high achieving in your family, or were you the golden child?

My parents are the classic Great Migration couple: born in the South, met in college, moved north for better opportunities. Education was definitely the number-one responsibility for me as a kid; I knew I could always get out washing the dishes if I said, ‘Oh, I have homework.’ People say that your favourite subject is the one you find easy, and English came naturally to me. Probably because I loved reading.

What were you reading?

I think I read all 80 of the Nancy Drew mysteries. I just loved reading fiction and I loved storytelling in general. When I was in high school, my English teacher gave me a copy of Toni Morrison’s, The Bluest Eye. It wasn’t on our syllabus; she just handed it to me one day, saying, ‘I think you’ll love this.’ If you’re lucky, you’ll have had a teacher like that somewhere along the way.

What about clothes, dressing up, expressing oneself through appearance? Was that something significant within your family?

My mother liked clothes, but she was very much what I’d call an ‘appropriate Southern lady’. She believed that you dressed properly for the occasion; even for travelling, you got dressed correctly, never in sweatpants and a T-shirt. My father is the same: a very appropriately dressed, dignified guy. His mantra is: your shoes should be polished, your suit should fit, your shirt should be crisp, your tie should be properly tied, and you should have a pocket square. Not necessarily because it’s about fashion, but about wanting to present your best face to the world.

Were newspapers important to them?

My parents were huge readers of newspapers and to this day my father must have his hard copy of the Detroit Free Press; fetching it each morning is his daily exercise. Growing up, I wasn’t so much focused on journalism as much as compelling stories, and the newspaper was a great source for them. I probably spent more time focused on the features section of the paper than the news.

Is that still the case?

It’s professional now, so I soak it all in, but I am still absolutely drawn to wonderful narrative and beautiful writing.

You’ve often mentioned the importance of narrative in your journalism, more than, say, the need for tenacious reporting or getting the perfect quote.

I do think there tends to be two types of reporters: the ones who love gathering the facts and the ones who love writing the story. I definitely fall into the latter of the two camps. I see journalism as a sort of fact-based line of storytelling, and when you talk about a narrative, it’s also a way of making a story more personal; emphasizing the psychology of people’s decision making, and the emotional depth that that entails.

You studied at Princeton followed by an MA in journalism, but tell me about your first instance of actually writing for a newspaper.

I’d already done internships on the news desk of the St. Petersburg Times in Florida, and the Detroit News. Then I got an interview at the Detroit Free Press, which at that time was known in Detroit as the ‘writer’s paper’. They offered me an internship, and I have no idea where I got the chutzpah, but I remember saying to the editor, ‘I’ve already done two internships; what I really want is a job.’ She called me back and offered me my first job, in the entertainment section.

Did this mean specializing in any particular domain?

It was general cultural writing, but I really wanted my own beat – to ‘own’ a topic that I could constantly explore and deep dive into – so I started carving out a kind of mini-micro-beat about Detroit’s up and coming techno and rave music scene.

‘The publicist looked me up and down and said – I can still remember her exact words – ‘Not every publication is important.’ I stood there speechless.’

Considering Detroit’s musical history, wouldn’t that have been quite an esteemed beat to own?

To be honest, it was more fun than esteemed. [Laughs] And the irony, of course, is that techno, while originating from Detroit, had its most sizeable audience in Europe. This would have been around 1989, and I have a vague recollection of going to clubs like The Majestic, or just random pop-up clubs where DJs played. The most prominent were Kevin Saunderson, Derrick May and Juan Atkins and Saunderson’s big hit, ‘Good Life’, appeared around then. I’d go and meet them and think, ‘You’re a good story.’

How did you end up on the fashion beat?

Robin Abcarian, who was the fashion editor at the time, became a features columnist and the newspaper needed to replace her. I just thought, ‘Wow, this beat is available; I know nothing about fashion but, you know, I wear clothes. I’ve got nothing to lose; I’ll apply.’

Had you read many fashion magazines?

I had a friend who got W, which might as well have been written in Sanskrit. I had no idea, nothing, nada. I liked clothes, but that was it. So I consulted one of my high-school friends – my gay consigliere – who gave me a pep talk about who was who in fashion, and I put together a proposal and presented it. Unsurprisingly, I didn’t get the job because they were like, ‘Er, you know nothing about fashion!’ But they asked me to cover menswear part-time while continuing my other assignments. So my introduction to fashion came through menswear.

Did that immediately mean going to cover the shows in Paris and Milan?

Yes. It’s kind of amazing to think that at the time the Detroit Free Press not only had the budget for a fashion editor who went to Paris, Milan, London and New York twice a year, but it also had a secondary writer covering menswear in those same places. There were the resources available and it was deemed important. Robin Abcarian gave me a list of shows that were either ‘must-see’, ‘up to you’, or ‘you can skip’. Knowing nothing, that list became my bible. And I was told not to review, just to report: ‘Don’t offer up your opinion, just go and tell us what you see.’ Robin also gave the names of four other regional editors who were her pals on the road: someone from the San Francisco Chronicle, the Cleveland Plain Dealer, the Houston Chronicle and the Dallas Morning News. These women were lifesavers: so kind and welcoming and informative; they saved me from catastrophe.

Did you feel out of your depth?

I was deeply horrified! I am still scarred. We hadn’t registered properly, so I remember having to call all the Parisian fashion houses and use my sophomore French to get invites. No one knew who I was; it was a Detroit newspaper no one cared about; and we were late to the game that season. The invitations I did manage to get were either standing or in tenth row. It was basically a huge learning curve, and I cried in the privacy of my hotel room from the stress and the awfulness of it. But at the same time, I was in Paris!

Which specific shows can you remember attending in that first season?

Shamefully, it’s all a blur and I don’t remember any actual shows; what sticks out is the whole logistics of being there. I remember in Paris having to go to the less-than-salubrious Rue Saint-Denis to supposedly pick up an invitation for a show; on arriving, I was told to wait for what seemed like ages, then finally got called into this room where the publicist looked me up and down and said – and I can still remember her exact words – ‘Not every publication is important.’ I just stood there speechless, thinking, ‘You’ve had me come all the way here just so you can insult me in person!’ I turned and walked out. It was horrible, hideous, but I persevered.

‘I think the fundamental job of a journalist is to be the eyes and ears of the public. I’m not here to please the designers or the retailers or the publicists.’

Part Two

‘I try really hard not to drink

too much of the fashion Kool-Aid.’

By your own admission, you didn’t start out as a big fashion authority. Do you think that consequently set the tone for how you’ve gone on to write about the industry?

I saw myself as being in the room and being able to observe and talk to people about what they did, and try to understand it. But still to this day, I never feel like I am part of the fashion industry. I cover it, but I’m not part of it. I am part of the journalist community.

That’s a key distinction for you?

Yes, because I don’t make fashion happen. I have nothing to do with what consumers ultimately see hanging on store racks. My job is to help consumers understand how those things got there, to understand more about the people who make those clothes, what those people might be thinking and what inspires them; why this dress is $5,000, while that one is only $50; and if you’re not happy with the way it is being marketed and sold to you, how you can change that.

So your commitment is to the consumer – or at least the reader – not the fashion industry.

Absolutely. As far as I’m concerned, as soon as you start to consider yourself part of the machine that makes fashion, you won’t be very good at explaining how that machine works, or offering healthy criticism about that machine. I think you have to have a certain degree of scepticism; and I always say it is scepticism and not cynicism, because if you become cynical about what you’re covering, you need to find a different beat.

When Obama gave his final press conference in January, he addressed the members of the press directly, saying: ‘You guys have to do that hard work to get to the bottom of stories, and getting them right, and pushing those of us in power to be the best version of ourselves.’ Does his statement have any relevance in fashion journalism?

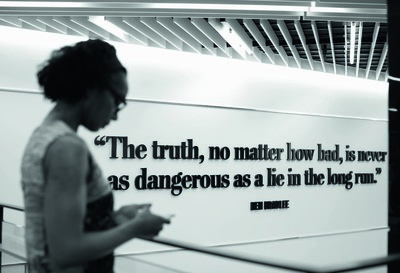

I think that the fundamental job of the journalist is to be the eyes and ears of the public. You are not there to please the designers or the retailers or the publicists. You are there to please the readers: to delight them, to inform them, to advocate for them, to look at things through a sceptical lens so they have the information that they need to process what fashion is presenting them.

Can you give me an example.

How that ad campaign is manipulating them. Why the cover of that magazine influences how they define beauty and value and femininity. It will hopefully enable them to become better consumers; certainly if they are concerned about issues like sustainability or labour practices.

What are your thoughts on large parts of the fashion media – from glossy monthlies to Instagram influencers – being quite openly ‘bought’ or neutralized by fashion brands?

I view it with a certain amount of curiosity and bemusement. I mean, I certainly understand the role of magazines and the way that magazines see themselves within the fashion universe, and that is very different to the way that newspapers do. In any one magazine, there can be terrific stories and essays about political and social issues, while the fashion editorials operate in an almost parallel world.

But hasn’t that always more or less been the case?

I think there might have been a period two generations ago when readers had a highly nuanced understanding of the media, but things have changed so much and so rapidly that I just think that people who are reading magazines or looking at blogs and Instagram feeds see it as one big blur of information. Whether it’s political reporting or fashion reporting, we should be concerned when people are unable to make distinctions between what is independent journalism, what is advertorial writing, and what is just straight advertising.

Is the ubiquity of social media a healthy thing for an established journalist? Or do you think it’s becoming increasingly difficult to cut through the noise of the often-polarizing personal opinion that’s now in the public arena?

It would be wonderful if it was civil and delighted expression of opinion, but oftentimes it is a really mean, how-obnoxiously-can-I-say-something kind of discourse. Because it is so provocative, it attracts eyes, and triggers this immediate but generally short-lived conversation. I think the longer, more in-depth, more interesting conversation is the one that exists in the grey zone, where something isn’t necessarily the best or worst thing that I have ever seen.

To what extent does the publication you’re writing for – and its readership – influence the way you report fashion?

I think that the person I was writing for changed when I joined the Washington Post in 1995; in part, because it is both a local reader and an international reader. The Post has scope, whether it is online or in print, and so if I were to describe the average reader, it is someone well educated, very curious, opinionated and deeply engaged with their culture. And I suppose I also see that person as being sceptical about fashion. I don’t see myself preaching to the choir, although there are definitely members of the choir who read. Unlike a lot of a newspapers, the Post has never had a specific fashion section, and I’ve always really liked that. I like the fact that fashion stories are in the Style section, so they jockey for position with stories about film or politics or television. It means that they’re being seen by people who might accidently stumble across them.

‘We should be concerned when people are unable to distinguish between journalism, advertorial writing, and what is just straight-up advertising.’

Does that affect the subjects that you write about?

Definitely. The Post’s readers aren’t particularly interested in who is up and who is down in the industry; they are more interested in how that person might impact their life. I remember when I pitched a Dries Van Noten profile and I said to my editor, ‘We should write about him because his clothes are breathtaking, and that is enough.’

In the show notes for Marc Jacobs’ final Vuitton show, he wrote, ‘Connecting with something on a superficial level is as honest as connecting with it on an intellectual level.’ Similarly, do you think your writing has a responsibility to simply entertain?

I think it has to! That is the primary goal. I mean, you are never going to inform someone if what you’ve written reads like a computer manual. It has to be entertaining in order to capture anyone’s imagination. Sometimes, there is no greater pleasure than going to see a collection that is really just a pure visual delight; I don’t think any less of a collection that is just pure pleasure than I do of, say, a Comme des Garçons collection, which is an intellectual brain-twister. I applaud those designers who can give people that pure pleasure because it is no easy feat.

In any given season, you’ll see well over a hundred collections. Do you find yourself wanting to write about, say, Balenciaga or Comme, because they’re considered by other critics to have shown stand-out collections, or are you homing in on more socio-politically engaged themes within those collections, regardless of popular ‘fashion-industry opinion’?

I am most interested in and most excited to write about collections that make me think about things far beyond the runway. Designers like Thom Browne and Rei Kawakubo sort of love you to extrapolate whatever you want to out of their collections and shows, which I find both frustrating and energizing! But above all, my antenna is attuned to those collections that allow me to talk about fashion in the same way that you would talk about an intriguing painting or a provocative film. I don’t necessarily think that it has to be a complicated political tango. I remember several years ago I was at a Dolce & Gabbana show; they did a little preview with this long, complicated tale about the mood in Italy, and migration. When I actually saw the show there was barely any evidence of that narrative, yet it was absolutely gorgeous. I remember writing that you don’t always need a long rambling existentialist tale to justify beauty, because, as I said before, beauty is quite often enough.

Do you ever find yourself tempering your criticism, knowing that harsh reviews might impact people’s lives – whether it’s the designer or the lesser-known individuals involved – or because getting banned from shows might be counterproductive?

I try very hard not to, but I am also mindful that if something is critical, it shouldn’t be personal. I don’t presume to get into a designer’s head and say, ‘This is what the designer was thinking,’ unless that person’s actually told me that is what they’re thinking. I just try to see both sides of a situation.

Have you fallen out of grace with designers or brands?

I wrote a piece about Rodarte, with the headline ‘Does Rodarte Exist?’ By that, I meant, is this a traditional fashion brand that is set up to actually build a profitable business through its runway productions and the clothes it is putting out there? My reaction was no, and for many reasons that I detailed. But I did try to acknowledge that what these designers are doing is very satisfying to them – and that shouldn’t be discounted by any means – but it doesn’t make anything like a sustainable business.

And how badly did they take the piece?

Well, I don’t think I will ever see another Rodarte show in the flesh! But I think it was an important story to write for the readers. I think Rodarte is a really obvious example of the smoke and mirrors and the mythology of fashion, which sometimes obscures the fact that fashion is a business and has to function. What readers are seeing on the runway and in photos shoots isn’t actually real – it’s an illusion. Ultimately, I try to ask the questions that readers might have, and try to anticipate when they are going to raise their eyebrow in scepticism, and have an objective answer for that. And I try really hard not to drink too much of the fashion Kool-Aid.

‘I despise words like fashionista; I don’t even know what it’s supposed to mean. I think it’s belittling at best and meaningless at worst.’

One of the things that strikes me about your writing is that there is a conspicuous absence of ‘fashion talk’; no ‘fashionista’ or ‘the frow’.

I try really, really hard not to use that. I’m always reminded of why when I pick up a sports story; when I get half way through, they’ll have lost me because I don’t know what a ‘pick and roll’ is, and no matter how many times people have explained this to me, I still don’t understand. I find it’s better to just say what something is, rather than rely on the vernacular of fashion. And besides, I despise words like fashionista; I don’t know what that’s even supposed to mean. I think it’s belittling at best and meaningless at worst. You know, words are just as relevant to someone who covers fashion as to someone covering politics, because at the end of the day, you try to let your reader in on the truth as well as you can report it.

Is the increased emphasis on fashion reporting as seen through the prism of business a good thing? I guess there are those who’d argue it’s one more nail in the creative coffin.

It’s certainly a great aspect to report on. It’s always intriguing to me to see what consumers latch on to, and when things really sell. Saint Laurent under Hedi Slimane was a great case in point. Based on the numbers, he really struck a chord with consumers, whether it was the runway collection or the classic collection. As a critic though, I would go look at those collections and not necessarily have a ton of positive things to say. But the story stopped being ‘Why or why not this is a good collection’, and became more a question of, ‘OK, the collection is what it is, so why is it connecting with the people the way that it does?’ I think that the financial part of it is key to moving the story along; it forces you to ask different questions.

So the consumer experience outweighs the industry interpretation.

I don’t know if it eclipses it, but it adds a whole other layer to the conversation; it keeps the industry from talking to itself. In the case of Saint Laurent, it didn’t change my opinion as a critic about the collection – I still thought aesthetically that its proportions were off, and it felt derivative – but there was now this other aspect where the consumers thought it’s great and were buying it. And so my question becomes, ‘What is it that’s making those aesthetic considerations no longer viable, or less important.’ Something has changed and to me that is intriguing. I want to figure out what is changing in the eye of the consumer because that has ramifications for Saint Laurent, and other brands to come, and fashion as a whole – for better or worse.

Part Three

‘Trump has been very shrewd

about the way he dresses himself.’

Over recent years, you’ve become increasingly known for writing about the appearance of politicians. Was that something that always intrigued you, or did it become a kind of default specialist subject since joining the Washington Post?

With the Post, it’s impossible to be in Washington and not have that seep into your mindset. And once I’d explored it, I realized that it was particularly interesting and it became ever more apparent to me how much appearance and image and storytelling, and this notion of costuming, plays into this world of politics and the way that we view and respond to public figures.

Can you recall an instance when this first became apparent?

One of the first stories about that came at the very end of the Clinton years. Washington fixer, Vernon Jordan, is this tall, black man; very wealthy, friend of many presidents, and is known for his style. Turnbull & Asser shirts, ties from Charvet, beautifully tailored suits, and so on. He was going to appear before this congressional hearing and I essentially wrote about how he was inevitably going to be the best-dressed man in the room. Part of his choices about what he wore, and the way that he dressed in public, was very much rooted in the idea that he was often the only black man in the room; his clothes were part of his way of collaring control. That opened the door for me to a point of view that I found really interesting. During that same period, when Hillary Clinton had to appear before the grand jury, she did so wearing a coat that had a sort of abstract print on the back. There were all these commentators who kept on referring to this print as a stylised dragon, saying, ‘Why would she wear such a coat?’ I remember calling her press secretary about it, and he took a photograph of the back of the coat and e-mailed it to me. The print was completely abstract; there was no dragon! So I wrote this piece about how people just see what they want to see. It was fascinating, the way that fashion could be used to alter people’s perceptions about what they were seeing; and how this could influence whether they saw someone in positive or negative light.

‘Appearance doesn’t change fact, but it certainly can alter the way in which we perceive the fact; sometimes, it alters whether or not we believe in it.’

You concluded a recent Washington Post piece about the appearance of politicians with the line: ‘Image is always secondary to substance. It may briefly distract from a narrative or add to it. But surely, it can’t change it.’ Tell me more about that.

Appearance underscores something that is being said – a message. It can distract, it can contradict that message, but it doesn’t fundamentally change the messenger. I think that’s something we wrestle with all the time; this idea that certain people are taken more seriously or deemed more legitimate because of their attire. It shapes the message, it shapes how we perceive the message, but it doesn’t change whether that message is true or false. Appearance doesn’t change fact, but it certainly can alter the way in which we perceive the fact; sometimes, it alters whether or not we believe in it.

Give me an example.

One Sunday, a few years ago, the United States’ security colour levels went from yellow to orange. Suddenly, there were these quick recalls to news conferences that involved the mayor, the police chief and the fire chief in both New York and Washington D.C. In New York, the three players were dressed in suits. Here in D.C., the mayor was in casual clothing, the police chief was in his everyday uniform, and the fire chief looked like he’d been at the mall with his kids when the news broke; he was in a very casual shirt and shorts. The whole point of these news conferences was to reassure people, and send out a message that said, ‘Everything is under control, don’t worry, go about your day.’ The facts in New York and the facts in D.C. were exactly the same, but because of the appearance of the trio in D.C., things looked less in control, less organized, less polished. It’s a good example of how appearance won’t necessarily change facts, but it can certainly affect how much faith we have in them.

How much of this is at play in the Trump administration?

There’s an incredible emphasis on appearance! It’s as if the appearance is going to change our understanding of, our judgement of, or our willingness to believe in the administration. And it’s like, hold on, facts don’t change whether they are wrapped up in a business suit or a Gucci cadet uniform.

It brings to mind the Post piece you recently wrote about Sean Spicer; how in his first official press conference he was wearing a huge, terrible-fitting suit and shirt, then later that same day he appeared in front of the cameras in seemingly sharper attire – as if he’d been advised to clean up his act.

After that piece was published, one reader sent me an e-mail that referenced a Renaissance painting. [Reading out e-mail:] ‘Sean Spicer’s ill-fitting suit reminded me of the portrait of Ranuccio Farnese by Titian, which is at the National Gallery here in D.C. You can find it on the nga.gov website. It states: “Adult responsibility came to Ranuccio when still a child, as Titian so brilliantly conveyed through the cloak of office, too large and heavy, sliding off the youth’s small shoulders”.’ It was such a fascinating and obscure reference, that’s why I love the Washington Post readers!

What about Trump himself in all this?

One of the things he has repeatedly referred to is how someone ‘looks the part’; he did it a lot during his hunt for a secretary of state. I think he does believe that. I mean, he is a prodigious consumer of television, and I think he does believe that visuals really matter in selling the story line. He personally has been very shrewd about the way he dresses himself: he wears these expensive suits that don’t look overtly expensive. He never looked too polished on his campaign trail, in a way that might cause a working-class guy to be suspicious of him. But then, when he arrived at the White House, suddenly he is wearing a pocket square, a little flourish of formality. I think it is all very subtle… well, actually not that subtle at all! I mean, when you consider the transformation of someone like Steve Bannon, who spent the bulk of the campaign wearing five shirts at once with the collars popped, and even he is in a business suit now. So, you know, there is a clear understanding of what power looks like.

You’ve often written pieces about Michelle Obama’s appearance and rapport with fashion. Will you be following Melania Trump in the same way? In terms of pure appearance, I guess she’s the first ex-model to become the First Lady.

Honestly, I don’t have an answer for how interesting Melania is yet, because we’ve seen so little of her thus far. My interest in the other First Ladies has generally focused on what they’ve worn to the inauguration, because the gown typically ends up in the museum.

‘I can only pray that no stylist was responsible for Kellyanne Conway’s inauguration look. I think that was a personal decision that went a little awry.’

Beyond that, is there any significance?

Well, whether it’s Jackie Kennedy’s Europe via America glamour or Michelle Obama rooting for Jason Wu – young and optimistic – there’s always this idea that the inauguration gown represents a kind of soft-focus advance peek at how the administration wants to be perceived, the shorthand they want to use to describe themselves.

Personal stylists have become increasingly present across many industries. To what extent are there stylists operating in the field of politics?

There are certainly people who advise and recommend, but other than at the level of First Lady – where someone is going out and getting dresses made or commissioned – it is not that extreme. But there are definitely people who are charged with making sure that politicians look polished and professional, but not too fancy.

Did that service extend to Kellyanne Conway’s inauguration look?

[Laughs] I don’t know, I can only pray that no stylist was responsible for that! I think that was a personal decision that went a little awry.

What do you make of the fact that American designers such as Tom Ford, Marc Jacobs and Zac Posen have been vocal about not wanting to dress Melania Trump? Or the fact that Nordstrom cut Ivanka Trump’s line?

I think it’s significant. It was a very polarizing election and this has been an administration that has unfolded like no other. Fashion isn’t exempt from the tumult that some of the other industries and the individuals in those industries feel. I think there are designers for whom fashion is the way that they communicate on the world stage, and they wanted to make their thoughts clear. I suspect there are probably as many designers who see dressing the First Lady as something unique and interesting and can separate that from the individual. They can focus on the role, the title and the historical nature of it.

A few years ago, Cathy Horyn wrote that, ‘There’s a danger of reading too much into the fashion choices of a person, particularly a public figure.’ Would you argue that today, on the contrary, it seems more important than ever to be examining these things?

For sure, I’d say that. It is more important now because we have become a culture that is so quick to judge, and to judge based on a glimpse, a word, a phrase, a gesture, so I think that public officials who are out to sway opinion are ever more sensitive to that reality. Look at Trump’s obsession with crowd size; for him, that visual is a statement of popularity and success. Of course, I do think we need to be cautious that sometimes a dress is just a dress, but we should be looking closely at the style choices of public officials.

We’ve already seen fashion becoming increasingly politicized over the past season. Is that a good thing? Misplaced? A fad?

I definitely think that fashion has the tools to engage politically – the reach, the stage, the audience – and I think that it has shown an intellectual capacity to do that, too. I don’t know fashion has an obligation to be political with what it presents on the runway, but I think it has an obligation to be relevant. In the same way that I think fashion has an obligation to be diverse and respectful of a wide range of customers. It has an obligation to be aware of the changing nature of global relationships.

Do you think it exercises that awareness in an appropriate way?

I tend to be surprised that, given the fashion community of people, it is often as reticent as it is to step forward.

Is that ultimately because business is business and the bottom line cannot be influenced or swayed by other factors? I mean, when you started writing about fashion in the late 1980s, it was already referred to as an industry, but these days it operates on a truly industrial scale – with a lot more zeros.

Well, you could argue that all those zeros are just a measure of fashion’s scale. But I do think that it’s interesting that the tech community has been much more aggressive in speaking out about some of the things that are happening politically than the fashion industry has. I couldn’t imagine the tech industry would be anymore adversely affected or morally controlled by things that are coming down the pipe from the Trump administration than the fashion industry would be. Republicans use iPhones and Google. So, to argue that fashion doesn’t want to offend its customers doesn’t add up. I think it’s just a matter of how the tech industry sees itself within our culture; I think tech sees itself as a leader in terms of its consumers.

‘Fashion wants to be free to claim any kind of inspiration as its own, but it’s rarely willing to take on the responsibility that comes with that privilege.’

I think what’s significant is how many individuals in fashion were very outspoken, yet the brands those individuals are associated with have for the most part remained tight-lipped.

I agree that as a whole the industry hasn’t spoken out. Fashion hasn’t had its Meryl Streep moment.

Does that disappoint you?

Well, I don’t know if I have any more of a vested interest in fashion speaking out than tech speaking out. As a reporter in this industry, it makes me want to consider yet again how fashion perceives itself on the world stage. I think fashion is a deeply conflicted industry, in that it has global reach and enormous influence in how we define the individual. Yet at the same time there is often a tendency for fashion to disavow any responsibility and to disavow its impact.

Can you give me an example?

I remember Ralph Lauren showing a collection filled with grey flannel and bankers’ stripes in 2009, in the middle of a global economic crisis. You sort of ask yourself, ‘What is the appropriateness of this product in these times?’ In Ralph Lauren’s case, he is just going back to part of his company’s vernacular, something he’s done a million times before. But, you know, once you put it out there into the world, how does it look against that backdrop? Ultimately, fashion wants to be free to embrace any kind of inspiration and to claim that as its own, but it is not always willing to take on the responsibility that comes with that privilege.

Why do you think that is?

Because fashion is made up of human beings, and human beings are far more inclined to take advantage of things than take responsibility for them!