Brendan Kennedy on why marijuana could be luxury’s new frontier.

By Xerxes Cook

Photographs by Juergen Teller

Brendan Kennedy on why marijuana could be luxury’s new frontier.

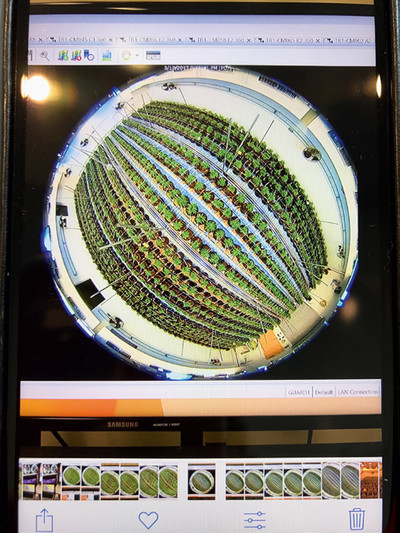

The backdrop for Juergen Teller’s portfolio, Waiting for Rihanna, is a 60,000-square-foot indoor marijuana facility off the west coast of Canada. It is owned by Seattle-based Privateer Holdings, a private-equity firm that has been working on the production and distribution of legal medicinal marijuana since 2010. Steered by CEO Brendan Kennedy, the company’s portfolio has expanded in line with shifting attitudes towards cannabis throughout Canada and the US, and now encompasses the website Leafly – which ran the industry’s first full-page advert in the New York Times, when New York state legalized medical marijuana in 2015 – and most notably, the Marley Natural line of buds, body-care products and smoking accessories made in conjunction with the late singer’s family.

This changing legislation and the accompanying shift in mainstream perceptions of the plant has seen legal marijuana become the country’s fastest-growing industry, according to one cannabis-business research firm, with US sales projected to reach $22 billion by 2020. Marley Natural, marketed as a lifestyle brand with creative input from Heckler Associates – the ad agency that gave Starbucks its name and mermaid logo – and Bob Marley’s former art director, Neville Garrick, has been featured in reputable media outlets such as Business of Fashion and US Vogue, under headlines speculating that marijuana might just be the luxury industry’s next big opportunity.

With his aim to take Marley Natural as mainstream as the all-conquering Seattle-based coffee company, Brendan Kenney sat down with System to talk about the power of marketing, working as a heritage brand, and the politics of being in an industry that remains illegal under US federal law.

Xerxes Cook: How does one become the CEO of one of the world’s largest legal-cannabis companies?

Brendan Kennedy: After Yale, I started at a new subsidiary of Silicon Valley Bank; we had clients who were working on interesting things in software and biotech science. One day, the owners of a medical-cannabis company walked into my office, and I thought that was interesting. It was something I knew nothing about, but I always felt that whatever my next entrepreneurial adventure was, I wanted it to be big. And then a couple of days later I happened to hear an NPR show about California’s Proposition 19 [the Regulate, Control and Tax Cannabis Act of 2010], and I sort of took it as a sign.

So you quit your job at the bank, called up your two buddies, Michael Blue and Christian Groh [Privateer CFO and partner], and convinced them to take this leap into the unknown with you?

Yeah, that’s pretty much how it happened! [Laughs] The three of us had to talk ourselves into it – this was different than just leaving our jobs to start up a new Twitter. There was an element of reputational risk. We had to have those conversations with our spouses and parents, and my parents are more Frank Sinatra than the Grateful Dead.

I’ve read that you were initially very sceptical about medical marijuana. What changed your mind?

I was extremely sceptical of the concept of medical cannabis and of its efficacy. It just sounded too good to be true; it sounded like a panacea. And that was how I felt until we started doing research. It wasn’t just one single moment that changed my opinion; it was a series of encounters with lots of different people. We talked to cannabis growers, retailers, patients, pharmacists, physicians, activists, lawyers and political campaigners – but it was the combination of patients and physicians that changed my opinion. There was a fire chief in California, a staunch law-and-order person, who had an extremely nasty form of cancer. He used medical cannabis in the final six months of his life and he spoke about it as being the one thing that worked in helping him manage his pain. That is just one example. The first time you have that conversation, not all your scepticism goes away, but the tenth time you have it – whether it is with someone who is using cannabis to treat pain in the final months of their life or someone who is the mother of a child with epilepsy – you can’t remain sceptical anymore.

What was the most surprising or convincing finding from your market research?

We were really data driven, so part of our pitch to investors at the time was about the eligibility of it. Interestingly, a lot of the polling at that time in the US matched that of gay marriage, almost identically, and that was fascinating to us because we saw the inevitability of the end of cannabis prohibition. There are a lot of religious groups and political groups opposed to gay marriage, but we couldn’t find any groups who opposed cannabis legalisation.

How would you characterize your investor’s motivations?

I would really break it down to when they invested. In our initial round in 2012 and 2013, we raised $7 million, and most of those investors saw the business as a form of political activism – most of our investors were looking for financial return, but all of them were looking for a social return. It was the first time I’ve ever had to manage investor expectations.

There’s a line in a great 2013 New Yorker article exploring the hurdles facing the legal marijuana economy that says you and your partner Michael Blue ‘disdain iconography involving cannabis leaves or Bob Marley’. What happened?

In one of the first meetings we had at Privateer, we made a list of all the clichés around cannabis we didn’t like, and one of those was that stylized imagery around Bob Marley and cannabis – it was one of the things that needed vast improvement. Then in February 2013, we were approached by the Marley family, who were intrigued by how we were talking about and approaching the industry. We spent a lot of time with them – his children, grandchildren, and his wife, Rita – learning about his beliefs and thoughts on cannabis. And I realized my initial conceptions were misconceptions. After a process of almost two years from our first conversation with them, we launched Marley Natural. The challenge is to build a global brand – and which is an expensive and time-consuming process – distanced from the ubiquitous clichés, which elevates the industry. To design products that are timeless and respectful of Bob Marley. To educate people and describe cannabis in a mainstream way – because its use is mainstream.

How are Bob Marley’s values of social justice and respect for nature seen in the brand’s social initiative, Rise Up?

Rise Up is an important aspect of the brand. Close to 750,000 people a year in the US are arrested for cannabis possession and distribution – disproportionately African-Americans and Hispanic-Americans. The idea behind Rise Up is that it’s important to the industry as a whole that those who have been most harmed by prohibition somehow reap the benefits from its end. We have worked with the Minority Cannabis Business Association to expunge the criminal records of 30 people who were convicted for cannabis possession or distribution. And we plan to do it again. We also want Rise Up to give back to Jamaica, and so we are working on small agricultural projects there. The brand itself is steeped in education and social activism – what Bob Marley would advocate as the plant’s positive potential for the Earth.

People can be sceptical when brands engage with politics. Is this more than just business for you?

It is. We have 350 employees in seven US states and seven countries, and they are smart, professional people who are motivated to fuel change. We all believe success will be when people around the world aren’t being arrested for possessing a plant. We also believe that there are huge opportunities to produce plant-based pharmaceuticals that don’t have the devastating effects of opioids.

This leads us to Tilray. How does one get become the only American company with a licence to grow and distribute medical marijuana globally?

With Tilray, we have a federal licence from [government ministry] Health Canada in Canada. We’ve built a pharmaceutical-grade production company whose products are distributed to 20,000 patients registered with Tilray in Canada. Then we also produce products for export for commercial purposes, typically to pharmaceutical distributors that dispense our products to pharmacies. We also export for clinical trials around the world. At the moment, two in Australia – one for chemotherapy, one for epilepsy – and one with a children’s hospital in Toronto focused on epilepsy. There is also compassionate use, for a single patient who for medical reasons is allowed to use cannabis, and we ship directly to them where they are.

‘The challenge is to build a global brand distanced from the ubiquitous clichés, and to design products that are timeless and respectful of Bob Marley.’

Do you run clinical trials at Tilray?

Not by Tilray at Tilray. We have run a few clinical trials, and we are working on a brain tumour clinical trial, and in that project, clinical researchers did some initial tests on mice that had these types of brain tumours. We will be exporting the formulation from Canada to the EU for that clinical trial.

Is Marley Natural cannabis also grown at Tilray, or are Marley products produced within the state they are sold in as you can’t ship across state or national lines?

Tilray is a pharmaceutical facility. In the US, Marley Natural doesn’t grow cannabis – we source and support local farmers who are experts in growing this product.

I don’t know your personal politics, but were the 2016 election results bittersweet for you? Trump was elected, but eight states voted to legalize recreational and/or medical marijuana use…

In October, I thought maybe four or five states would legalize marijuana in some form, but not eight. On the campaign trail, Trump said that he supported medical cannabis 100 percent; 90 percent of Americans think that marijuana should be legalized for medical reasons; 70 percent of Americans oppose federal crackdown on cannabis laws; and 60 percent support cannabis legalisation. The industry supports 125,000 jobs and going after it would just empower the black market. So I am pretty optimistic about the industry’s long-term prospects.

Is this your dream job?

For me, the dream part of this job is working with so many smart people and so many investors who see the end of prohibition as inevitable. The dream is that someday the big wall of cannabis prohibition will topple over, and I will be proud to have played some part in that.

One last question: do you get high on your own supply?

Far less frequently than you could ever possibly imagine, fewer than a handful of times in the last year. The office is a lot more boring than most people might imagine. And between the travel, and the fact I have small children, my hands are kept full!