Interview by Jonathan Wingfield

‘We’re now moving beyond quantitative metrics and using AI tools to slice the data down to reveal what people are really saying about brands – going beyond sentiment analysis, which is just ‘positive’ or ‘negative’, to something that can actually guide brand strategies. For example, across all the fashion media and social coverage of your recent show in Paris, were people describing your brand as ‘innovative’? Or ‘elegant’? Or ‘sexy’? If your brand positioning is meant to be ‘young, fresh, cheeky,’ but the conversation is skewing toward ‘heritage’ that tells you something. You might have had the highest Media Impact Value, but if the narrative doesn’t match your intent, that’s a brand alignment issue.’

As fashion grapples with fragmented platforms, shifting audience behaviour, and the pressure to quantify visibility, Launchmetrics has become a quiet force in the background – transforming how success is measured, stories are shaped, and decisions are made. Since forming in 2016 through the merger of Fashion GPS, a platform that supported PR teams in managing samples and invitations, and data start-up Augure, the company has evolved into an indispensable partner to brands navigating the increasingly complex intersection of culture, content, click-throughs and commerce. Its proprietary metric – Media Impact Value (MIV) – has redefined how brands understand the return on media exposure. Rather than relying on outdated equivalents, MIV assigns a real-time monetary value to coverage across print, online, and social platforms, factoring in nuances like audience quality, platform authority, and regional impact. A Gucci mention in Vogue is not the same as one in the Daily Mail, or indeed a pair of horsebit loafers featured in a Bollywood influencer’s Instagram post – and Launchmetrics quantifies those differences.

This granularity has become critical in an industry where success often hinges on intangibles – mood, gut instinct, cultural relevance. Launchmetrics turns those instincts into actionable intelligence, whether it’s deciding who sits front row (and why that seat might now be worth $77,000), or determining which influencers and media voices actually deliver ROI. The company, it says, now works with 85% of brands showing seasonally across New York, London, Milan, and Paris fashion weeks – supporting global luxury houses and emerging independents alike. Through strategic acquisitions – from backstage photography provider IMAXtree to influencer platforms in the US and China – Launchmetrics has steadily built a global infrastructure. In 2024, the company itself was acquired by Lectra, a French software company, further expanding its reach. But at its core, Launchmetrics remains defined by a core principle: data is only valuable if it’s clean, contextualized, and decision-ready. Internally, the company is structured around this commitment to insight. Alongside its business and marketing teams, there are dedicated data specialists working on everything from algorithm development to brand disambiguation – making sure, for example, that Coach the fashion brand isn’t confused with coach buses or Celine with Céline Dion.

“It may not be the sexiest part of the industry,” says Launchmetrics’ Chief Marketing Officer Alison Bringé, “but it’s becoming one of the most essential. Our clients need clean, specific, relevant data. That’s what helps them act with confidence.” In the following conversation – recorded shortly after Paris Fashion Week concluded, and just as Launchmetrics was publishing its data findings for the Autumn/Winter 2025 show season – Bringé sat down with System to unpack what’s really cutting through in today’s fashion-media landscape (hint: it isn’t just visibility, it’s insight) – and explain why custom metrics is fast becoming one of fashion’s most valuable currencies.

Jonathan Wingfield: To start, could you give a sense of how Launchmetrics works behind the scenes? You’re pulling data from so many different places – social media, editorial, influencers, backstage imagery – but how is that information gathered, verified, and made meaningful, into something brands can use?

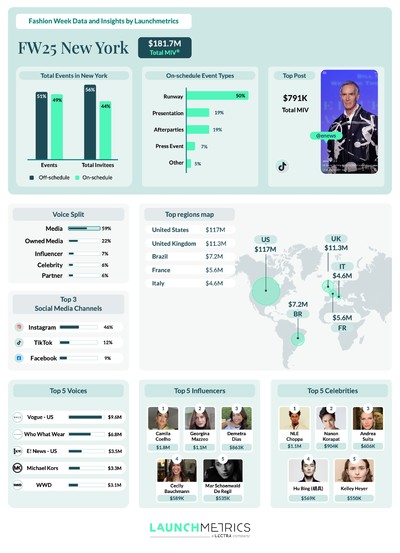

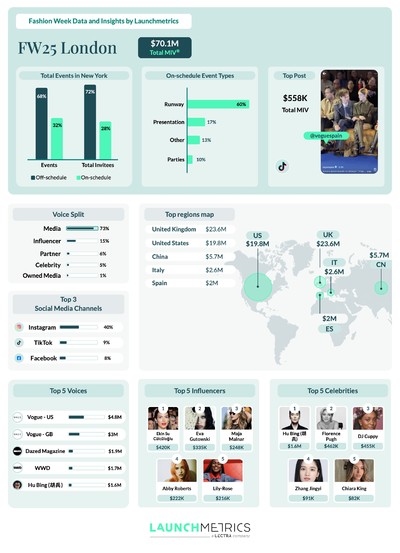

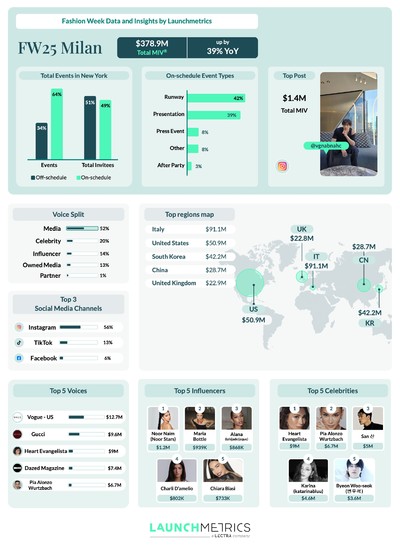

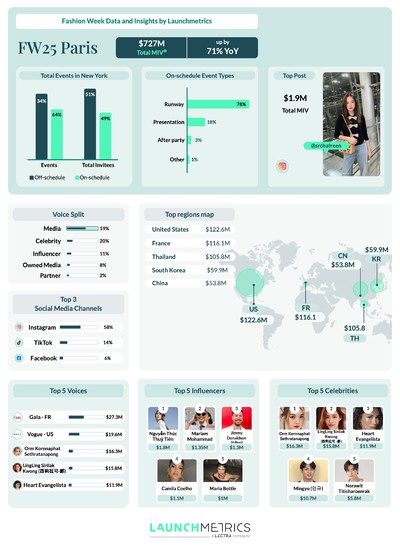

Alison Bringé: Let’s approach this in two ways. Firstly, by exploring the kinds of data that we monitor, across print, online, and social media. While a lot of print monitoring remains quite un-technological, because we acquired two print-monitoring companies, we have digitized data from about the last 20 years. Then we’re monitoring thousands of online publications in detailed ways. For example, things like slideshows are really important. Like ‘The Ten Looks from Paris Fashion Week’ or ‘The Best Red Carpet Looks from the Academy Awards’. When a brand is featured on Vogue.com, we’re not just monitoring the first photo of a slideshow, we’re looking all the way through, because a brand may be featured on the 12th slide, and they still need that data. So we’ve had to think about those types of smaller considerations – specific to our industry, and important to our customers – as we’ve been building our technology systems. And then of course we monitor social media. So we have an official API [Application Programming Interface] with most of the Western publications. Then in China, we’re also monitoring platforms like Weibo, WeChat, RedNote, BiliBili. From that, the MIV algorithm takes all of those different posts, articles and interactions, and helps quantify them. So we look at both traditional metrics that you would see in AVE [Advertising Value Equivalent] or EMV [Earned Media Value] to reach engagement, audience size and so on. Then we look at more qualitative metrics that consider content quality and authority. From there, we’re able to harmonize the difference of a New York Times article with a Vogue.com article with a video on BiliBili, and assign a dollar, yen or pound value. But to the other part of your question: what useful information and analysis can we glean from that monitored data? We have our MIV algorithm that has a lot of data and a very specific use case. I can tell you that, for example, across the four fashion weeks this season, the number of official shows decreased by -23%, and we saw a -16% decrease in the overall number of invitees.

Did that decrease impact the MIV of the fashion industry as a whole?

Interestingly, when we did that analysis, we could see that MIV had actually increased. So this season could be defined by the concept ‘work smarter, not harder’. Brands are paring down how many people come to their shows, but they’re still trying to make every seat work for them. We feed all of this into a data lake that manages all of the data coming in and out of Launchmetrics. That allows us to slice it and dice it in many different ways so that, yes, I can tell you insights about fashion week, but then I can also have, let’s say, a premium denim brand call me and ask: ‘We’ve been doing a lot of sample send-outs – are sample send-outs still important? Do people care about them?’ And I have the capability to say, ‘You’re actually sending out two times more samples than somebody else.’ Or I can say, ‘You’re getting more MIV than a competitor brand that sends out two times less samples than you.’ It’s really important that we think, ‘OK, we have all this data. Where does it go? What do we do with it?’ I think data is maybe one of the most interesting things happening in our industry right now, but so many people are paralyzed by it – because they just don’t know where to look. The sample send-out thing, too. Nobody cares about samples anymore, but it’s such a health check on your brand to compare that with actual coverage. But I think a lot of brands don’t have the time or the capacity to manage that. So yes, we provide a service to brands, but then the partnership side for me comes into it like, ‘What can you tell me? How can I build out a more focused marketing strategy based on data analytics?’

‘Data specialists work on brand disambiguation, making sure that Coach the brand isn’t confused with coach buses, or Celine with Céline Dion.’

Does Launchmetrics provide brand CMOs with streamlined data along with overarching narratives or analysis? Or is it more a case of delivering the data and letting the brand interpret it themselves? Do you find that clients typically want that narrative, or are they just looking for the raw insights?

Theoretically, most of our client brands look at their own data, and make their own assumptions. But many of them will ask for a post-event report after fashion week, presenting all their data along with our takeaways. On top of that, brands ask us for the same type of Paris Fashion Week general report that we send out to the press, because they obviously want to know how their competitors are faring.

What specific things are brands asking for right now?

There’s the industry landscape report, which presents the trends that we see coming out season after season in the industry – not just related to fashion week, but holistically throughout the year. Then the campaign reports are pretty big, and now we’ve formalized the ambassador reports. Brands obviously pay significant sums to celebrities and influencers, and while they’d previously been measuring what that person directly generated for their brand, they weren’t connecting it with the broader virality of the conversation. Now we’re offering them the capability to measure both the direct and indirect. For example, with Dior’s campaign featuring Natalie Portman, they can see not only what Natalie drives herself, but all of the conversations around the partnership. That’s really valuable, because brands are trying to quantify the success or failure of these actions, whether it’s a campaign, an ambassadorship, or a fashion show.

In Launchmetrics’ latest Paris Fashion Week report, it states that a single front-row seat at a major fashion show now has a MIV of around $77,000. How exactly do you quantify that?

Brands now say, ‘I want to see what the average MIV is for a certain celebrity or editor sat in my front row.’ And theoretically, when we were looking at how much MIV was driven at fashion week and what that could cost per seat, it was $77,000. Not every attendee generates that, obviously, because you generally wouldn’t put an MIV dollar amount on, say, buyers – they’re giving you a different type of ROI. So, in seasons where there might be time, budget or size constraints, you really need to prove the ROI of the 300 seats you have in the room – so it gives you a better perspective. It’s OK that this person doesn’t drive MIV because I’m getting this, or it fulfils that need. But at least it gives you more value than saying, ‘Sure, you can come with your three friends to my coveted fashion show.’

What are some specific ways that Launchmetrics’ data insights have helped brands evolve how they operate?

Lacoste is a good example. I think the MIV has brought so much clarity to their team. Being able to benchmark and measure all of the impact of their various media placements was quite critical for them to ascertain in what direction they should be taking their media strategy. Understanding which publications are delivering what, so they can be more precise with how they’re planning and deciding on those different partnerships – from both a commercial and PR perspective. Valentino is another example: I think what’s interesting for them is that it’s not just about Media Impact Value, it’s the ability to take that MIV and see it regionalized. It’s not enough to simply quantify reach and media impact, it’s also vital for a company of that scale to see where, granularly, things are working. Our brands can see what specific channels their communications are working best on; they can see which regions they’re cutting through in, which influencers or media publications are working well for them, and at what specific time of year. So they can really pinpoint: was it my fashion show that drove audience acquisition, awareness or conversion? Was it the seasonal campaign? A one-off PR story? The announcement revealing our new creative director? In the beauty space one of our customers is Pai Skincare, an up-and-coming clean beauty brand in the UK. They’re always thinking about the efficacy of their influencer partnerships because, of course, in beauty, influencers are so important. They have a strong ‘clean beauty’ message they need to communicate via influencers, and they’ve been able to refine their strategy based on which influencers can drive the best ROI. So, these three examples show different ways in which the brands can now reevaluate their marketing strategies.

‘Across the four fashion weeks this season, the number of shows decreased by -23%, and we saw a -16% decrease in the overall number of invitees.’

Do the platforms themselves – Instagram, X, TikTok and so on – come to you to better understand how the fashion and beauty industries are using their platforms?

They’ve all approached us, to be an advocate for them because they’re all fighting for market share. Over the years we’ve done projects with YouTube, TikTok and Meta. It’s our role, I think, to communicate to our customers the differences between these platforms. The platforms themselves don’t always agree that there is that much difference – they’re just competing for everybody’s voice – whereas we really see that they’re all different, and there’s a different goal for each one. We’ve done reports with them where we’ve said, we’re happy to partner and tell your story, but this is the story we believe our customers should be picking up. The YouTube story is about long-tail value. We know YouTube videos don’t really start generating their peak value until 30 days post-show. That makes sense to me too – I’m not sitting on YouTube waiting to watch a fashion show that just happened 10 minutes ago, right? But this conversation we’re currently having might trigger me to go to YouTube and rewatch the Kate Moss hologram that McQueen did 20 years ago. It’s a repository. So, one thing we’ve pushed back to the social-media platforms is: you can all coexist. It’s our job to educate our customers about what type of content works best on your platform, when they should be looking at those metrics, and how to improve them.

What surprising insights can you share about YouTube, Instagram or TikTok when it comes to how the fashion industry uses them?

Everyone in fashion is talking about TikTok because it feels new and fresh and big and everywhere… But it’s not. Sixty per cent of the value that fashion brands are generating on social media today is through Instagram. Why is that? Because it’s an established platform with huge audiences that have been around for a long time. Every recent season people have been obsessed with this idea that ‘TikTok’s so big,’ ‘it’s the fastest-growing platform’ – well, it’s the fastest-growing platform because it wasn’t here before. If you had zero followers yesterday, of course you’re going to have more today. And we keep on having to remind people of that. In fact, last year, we published a report about the value Instagram delivers – that’s where that 60 per cent stat comes from. The other big platforms were Reddit and YouTube before we even saw TikTok. Fashion people can get so caught up with a statistic, but sometimes it’s just vanity metrics. So I think it’s important for people to remember: what is that slice of the pie? And Instagram certainly remains the biggest slice for the time being.

In an era where misinformation and manipulation on social platforms are big concerns, what kind of scrutiny is the data that Launchmetrics provides subject to?

I think it’s definitely been a learning evolution for us. When we launched MIV [in September 2018], the first reaction was everyone thought it was really interesting. After that initial report, when we started sharing data with the press, there were so many questions because nobody else was doing it. No one understood. Like, is this even right? How can I state that Kim Kardashian was the biggest celebrity at the Met Ball? I think we did a good job of defending our methodology and how we construct our data. Because of that, I think we’ve garnered the respect of the industry. Because we have such strict methodology – for example, if you post something on social media and then three days later you edit that post, we won’t give you credit for the edited post. Because we know your post is now old news – it’s three days later. In fact, there are people who might criticize us for being too strict. Or some brands will say, ‘I need the data sooner, so I’m going to use this other data source because it’s available quicker.’ And we’re also OK to say, ‘Great – but we don’t think that’s ‘complete’ data. You’re not getting the full picture.’

One of social media’s great unknowns is algorithm changes. Do you have an inside track from the platforms themselves on when or how those changes might happen, and how they could impact user experience?

Luckily, we haven’t had a huge shift in a long time. Typically, as an API partner, you get a heads-up that these things are coming, and the platform explains to you why, so you can adjust. And we’ll do the same with our customers – we make announcements ahead of time. It’s really about helping them understand the before-and-after benchmark of Media Impact Value – ‘What was my MIV before the change, and what is it now?’ – so they can see the percentage of growth or decline. The final number is less important; it’s the benchmark itself that validates the data. I’d say the biggest change has probably been after the whole scandal about public data being used – not by us – but that whole social media thing. Since then, of course, there’s been a restriction on consumer data. I’d say that happened at a good moment, when brands weren’t looking at this type of data as much. If we still had access to consumer data in that very free-spirited way, and someone came to the luxury brands at, say, Paris Fashion Week and said, ‘All monitoring needs to stop,’ that would be more detrimental – because it was such amazing data to see how consumers were engaging. But I think in the world we live in now, these changes are so small that you can easily understand and digest them.

‘Even though New York’s industry reputation doesn’t match Paris, it still delivers strong Media Impact Value. It punches way above its weight for visibility.’

As more brands seek to become data-driven without losing creative intuition, how does Launchmetrics support that balance between strategy, creativity and storytelling?

Brands need people at the helm who are creative, innovative, big thinkers. But those people also need to have some data insights to get a feeling for where the industry is going – not just creatively. You can be the most creative designer, but if there’s a recession happening or if consumers are leaning towards a more conscious or conservative perspective, you also need to have that awareness. You can’t let it prohibit or limit your creativity, but it’s almost like dancing with no music. So I think the brands that are most successful are the ones that can balance the two. Dior, for example, has done an amazing job over the years of building a global network through localized social media. Being able to see the value of something like that is a really operational data point. But knowing that at a senior level means you can build great campaigns to target niche, individual markets through a channel that has now become the most important one to reach the consumer. It allows us to marry the creativity and voice of Dior in a hyperlocal way and know it’s going to be successful, because we have the right vehicle to amplify that amazing message. It’s almost like data can be the vehicle of your voice – you just have to figure out what that vehicle is looking to deliver.

We’ve touched on this already, but I’d love to go deeper. How do you think assigning a monetary value through MIV to culturally relevant moments is influencing how brands approach creative risk and storytelling during fashion week? Does this kind of valuation encourage more experimental, outside-the-box shows, or does it create pressure to only invest in what’s guaranteed to make headlines?

I remember when we launched MIV, we looked at a number of shows that season – that was when we still had consumer data. It was fascinating to see how many consumers were engaging with fashion show content. We’ve been working in this industry for so long and we sometimes get wrapped up in this bubble of fashion month. We’re going to go see our fashion family, travel to different markets… But this event that used to be just focused on B2B [business-to-business] has really become a vehicle for reaching B2C [business-to-consumer] at the exact same time. More than ever, fashion month is now a month-long marketing campaign for brands to speak directly to their customers. Do I think brands always need to go big or go home? No. But I do think it’s a really interesting moment to leverage the consumer. It could be anything – like when Ralph Lauren did his anniversary show. He did something very specific to the industry, but then also did something that paralleled the show in the store. So you could walk into the store and experience some of the fashion week elements. They had influencers activating at both the show and the store, driving people in and creating that connection with the B2C consumer. This season, if we look at Milan Fashion Week and how DSquared2 brought in Doechii to perform – it was amazing, and they saw their MIV increase 60 times year-on-year.

Do brands need to do this every season?

No, I don’t think so. But I do think brands need to think about their goal each season. I don’t think every season is about being this breakout consumer star. Brands are trying to have different types of relevance at different times. Sometimes it’s about having a strong collection that really speaks to the buyers you’re targeting, because you need to strengthen those relationships. Sometimes it’s about driving people into the stores, so you think about how to use the show as a vehicle to do that in the moment. Because of that, brands think about how they’re speaking to their audience, whoever that is, through the show. So, back to your other question, how is MIV influencing how brands approach storytelling during fashion week? In a sense, it’s all linked: Who am I casting? Who am I inviting? What does the show format look like? Sometimes we see brands doing parallel shows – one in Asia, one in the West – because they know their audience in China is particularly active at a particular moment, and they’re trying to reach them. That show will often be very consumer- or social-heavy, versus press-heavy. So again, brands always need to think: what’s the goal, and what’s the vehicle they’re leveraging to reach it?

‘YouTube videos don’t start generating their peak value until 30 days post-show. People aren’t sitting on YouTube waiting to watch a fashion show live.’

Just going back to TikTok. Paris saw the biggest year-on-year growth on TikTok this season, ahead of Milan and London. Does this say more about how different cities are leveraging the platform, or how media outlets are adapting their strategies?

We were asked by TikTok to do a report looking across all fashion, luxury, and beauty content. What’s most interesting about the TikTok value for fashion right now is that it’s the media voice leading the charge. In this moment where video has become king, the media is doing two great things. Unrelated to video, they’ve done a great job adapting to the changing landscape by using social media as the entry point to their publications. Today of course, people wake up and go straight on social media rather than read a newspaper, so social becomes your entry point to the reader. The media around fashion week has done a great job of saying, ‘OK, if TikTok is an emerging platform and video is key, we’re going to invest in our fashion week strategy on TikTok to drive those eyeballs to our website.’ And because of that, we’ve seen the media voice be really key on TikTok this season.

Will that just get bigger, or do you think it will plateau at some point?

TikTok continues to grow, so theoretically the Media Impact Value will too – it just means more eyeballs on that content. I guess we’ll see. Video is one of the most expensive things for publications to produce. If I think back to when many of the New York shows were held in Bryant Park, and how many media outlets had videographers and photographers on the riser, that number has really depleted over the years. I think the brands or media that can be more agile, raw and independent with the content they create – who don’t need expensive productions – will continue to be successful. Right now, it’s about how brands balance their need for perfection with raw, BTS kind of content.

That seems to align with the broader democratization of video content. These days, anyone at a fashion show can capture high-quality footage straight from their phone.

Absolutely. The technology has advanced so much that, in theory, everyone’s a potential content creator. Whether someone like Anna Wintour actually chooses to film is a personal or platform-driven decision, but it really reflects how much things have shifted over the last 10 to 15 years.

Let’s talk about the Chinese platforms. The increase in activity is 30 times year-on-year growth in Milan alone. What does this reawakening of interest from the Chinese digital ecosystem mean for global brands and how they organize their strategies?

I think it’s really a reflection of how brands are trying to cope with the Chinese slowdown. What sticks out in my head is the Dior example. When we first started looking at the value luxury brands were generating, Dior was one of the few that was present on every single channel and had local media channels. Nowadays, that’s much more common which, of course, means MIV is growing. I think brands are just being smarter about how they approach local markets, because they know they’re important and they know it’s not a one-size-fits-all approach. I think Covid helped expedite that too. If you remember when we were doing virtual shows, we had so many people calling in from China, and because of that, brands needed local channels to amplify that content. I think we’re finally at a place where there’s real ROI from those activities and I think we’re going to keep seeing growth.

‘The industry’s obsessed with TikTok because it feels new and young. But 60% of the value that fashion brands generate on social is still on Instagram.’

In Milan, brands seem to be leading the way on TikTok through their own channels, whereas in New York, influencers have taken the front seat. What does this contrast reveal about how brands are balancing control versus community when it comes to storytelling and social media strategy?

I think ‘control’ is the key word here, because you could go either way with the answer. The US is the hub of influencer marketing – it’s where it was born and where it’s done best. You could argue that China does really well with KOL marketing, but the professionalized version of influencer marketing really started in the US. Because of that, there’s more value there than in Europe – US influencers have more subscribers, bigger fan bases, wider reach. The US is just a bigger country, than, say, Italy or France or Europe in general, so that scales naturally. But again, control is the key word. For American brands, it’s easier to pass the baton – they’re much more open about how the brand is being communicated. That openness comes from the fact that influencer marketing has been around for so long there. In Europe, though, it’s still much more brand-led. Brands often have bigger budgets to invest in their own strategies, whereas American brands are more likely to pay someone else to create and deliver the message for them.

The Row bans smartphone use at their shows – presumably to convey a vision of luxury as privacy and exclusivity. Do you think we’ll ever move towards a post-content industry, where luxury brands start closing off channels and limiting visibility? Or is that approach more of an outlier, unlikely to become a wider trend?

People have tried it. Or they’ve taken that approach for a season. Back in 2010, Tom Ford had a ton of celebrities walking his Spring/Summer 2011 show, and nobody attending was allowed their phone. I don’t know if that’s going to work these days. It’s a bit like going to a wedding where they say, ‘No phones, please,’ and everyone’s just kind of frustrated. Because the phone isn’t just about you – it’s about the experience that person wants to capture. So it feels increasingly like a personal restriction, and in general, I think we’re in a moment where people don’t want to be told what they can or can’t do.

In a digital landscape that’s supposedly more democratized than ever, why do you think legacy titles like American Vogue still command such a disproportionate share of the MIV? What does that say about the enduring power of institutional media?

It’s a first-mover advantage – kind of like the comparison I gave you between Instagram and TikTok. It’s just that they’ve been around for so long. People aren’t saying, ‘Now that I have other options, I’m not going to read Vogue anymore.’ Everyone’s still reading both. Last year we did a study with Puck where we looked at all these brilliant collabs and partnerships – whether it was brands with influencers or brands with other brands. And the thing that resonated most was that even when, for example, it was announced that Pharrell was going to be the new men’s creative director for Louis Vuitton, they did that through their own channels – Pharrell to his 15 million followers and Louis Vuitton to its 55 million followers – but the most value still came from the media reporting on it. Not because there was any exclusive or even a press release sent out. It’s because the media is still key to amplifying every other voice. Vogue, as you said, is a legacy media brand that’s been around for a long time. So I think it’s the combination of both: the media being the most important voice across all voices, and Vogue being so powerful, notably with its US edition which has a bigger reach, wider circulation and readership, plus all that heritage and legacy.

‘The top-performing post authored by Gucci was one that featured one of their ambassador talents, Jin from BTS, simply arriving at the show.’

Launchmetrics has shed light on ‘content efficiency by platform’. How are brands rethinking their strategies to drive maximum impact per post instead of merely flooding social feeds? This taps into the classic debate of quality versus quantity.

One recent example we liked from Gucci at Milan Fashion Week was how a brand can approach fashion week in different ways – they might get an A-lister to do a bunch of posts, or post loads of their own content on every element of the show. But the top-performing post authored by Gucci was actually one that featured one of the talents, Jin from BTS, arriving at the show. We used to be in this place where brands would ask influencers and celebrities to post about them. But now, brands are thinking more strategically about what works on their own channels. Instead of asking influencers to post on their feeds, sometimes they’ll keep that content and post it themselves and we’re seeing that perform way better than just flooding their feed with lots of small posts. So it helps brands balance their strategy: ‘Do I need multiple posts to reach my MIV goal, or could I just do two really effective ones?’ I think you could also think about it as creating momentum. So if someone’s launching a new campaign, they might tease it out. Another thing that’s worked really well over the years is that slow drip of behind-the-scenes content leading up to a collection launch. It might take more posts to hit the same total MIV, but it’s about storytelling, too. So again, it comes back to asking: what’s the goal?

How does a metric like MIV capture the more ephemeral elements of a show – the mood, the energy of the room, those one-off viral moments like a celebrity entrance or a surprise protest? Can data really quantify the essence of a fashion moment?

Momentum is definitely measured by MIV. Just like how we can track a trend from when no one was talking about it to seeing it everywhere. MIV lets us see how that grew, and whether it’s regionalized – just in the US, say – or global. So I’d say yes to that. But can MIV tell you it was a bleak, sombre setting? No. What it can tell you is whether it worked. If nobody talked about it, that’s a pretty clear indicator of audience engagement.

Veronica Leoni’s Calvin Klein debut drove enormous media traction, with 39% of the brand’s total MIV linked directly to her name. Conversely, Gucci’s interim post-Sabato De Sarno show nearly doubled its MIV from the previous year. Are these creative leadership changes acting as a narrative strategy – where the designer’s story, their arrival, their exit, or even their absence becomes a primary drive of MIV?

I think we’re just in a moment where there’s a lot of change happening at once, so it’s part of the conversation right now. But potentially in a year’s time – once all those new designers have arrived at those houses – we’ll have this same conversation, and it’ll be zero per cent of the MIV. I don’t think we’re going to see a constant revolving door, but this does happen every few years, like when Daniel Lee moved from Bottega to Burberry, or with the Pharrell announcement. It happens here and there and then people move on.

‘When DSquared2 brought in Doechii to perform at their show this season, they saw their Media Impact Value increase 60 times year-on-year.’

Presumably, by the next fashion month, in September, we’ll see a significant spike in activity, given the unprecedented number of creative director changes happening across so many brands. Whether it’s coincidence or part of a bigger shift, there’s clearly a lot in motion right now.

Yes, and I do think people will want that headline: ‘So-and-so’s first collection, how was it?’ But eventually, I think people are going to talk more about the clothes. Even those ‘first collection’ stories will start focusing more on the collection –and the brand – itself.

In Paris, celebrities had a massive impact this season, with a 164% spike in MIV – with most of that coming from visiting Asia-Pacific stars. Is this something we’re seeing across all the fashion weeks, or is Paris where APAC celebrity power really peaks?

It’s been Paris for a while. Obviously, that’s where the biggest luxury power players are and they have the biggest budgets to invest in APAC. And I think it’s always been that way. I remember a Chanel show – about 10 years ago – when we first did the data and saw that name come up: G-Dragon. Chanel was already bringing him to shows. That was before anyone was really talking about APAC celebrities in this way. So I think Paris has always been ahead of the curve on this and now it’s just more amplified because of digital prowess and because we can actually quantify it more clearly.

When it comes to total global MIV, is there one person who consistently comes out on top? Someone who engages with fashion, attends shows, and is clearly, quantifiably the highest-performing celebrity in terms of ROI?

You could argue it’s someone like Jennie from Blackpink. She’s one of the top MIV generators – she has so many brand partnerships and a huge following. And then someone like Kim Kardashian obviously generates a lot of MIV, because she’s got a massive digital following too – and her family does a great job of amplifying that even more. So it’s hard to identify just one. The thing that’s always surprising for us is when you compare someone like that to a real Hollywood celebrity who has no digital following – you have to factor that in too. Like I was saying before, it’s about direct and indirect impact. There are a lot of ways you could analyse your question. I guess that goes back to the other question you had about whether people question the data. I think people often don’t realize that data isn’t actually black and white – it’s more about what you’re trying to understand.

When it comes to celebrities, what do you think most brands are actually aiming for? Is it about audience acquisition, conversion, a mix of both?

I think there are a few things. One thing we’ve already started testing with our customers – because this is such a big conversation – is how different voices influence different markets. I think brands want to understand how voices influence different places. Interestingly, the whole K-pop phenomenon has become a globalized phenomenon; these local stars are now generating value everywhere. So brands want to figure out how they can make their dollars work harder and push those boundaries. If you think about how Tommy Hilfiger brought all those K-pop stars to the Met Ball last year, that’s something you’d never have seen 10 or even five years ago. So it really shows how much the conversation has changed. The other question we’ve been getting a lot lately is tied to how brands measure ‘sentiment’. A few years ago, sentiment analysis became really popular because people thought it would help answer some of these data questions. Like, ‘OK, my MIV was 10 million, but was it positive or negative?’ So everyone wanted sentiment analysis. We started doing it, but quickly realized that it doesn’t actually tell you much. It just says, ‘This article was positive.’ But what was positive about it? Was it the product? The article itself? Your brand’s role in that article? It’s not detailed enough to move you from ‘so what?’ to ‘what now?’ So one thing we’ve started working on is a qualitative analysis service for brands. We have a few different ways of doing it. One of them is brand perception analysis, where we look across a brand – or a group of 10 or even 100 brands – and map them against key industry pillars. These are a mix of geopolitical issues and style-driven characteristics and pillars we’ve defined internally at Launchmetrics: it could be innovation, heritage, diversity, sustainability, elegance. We now have the ability, through LLMs [Large Language Models], to process all that MIV data and provide deeper insights. The LLM is basically an AI tool that allows you to process huge amounts of data to give you more qualitative analysis. Think of it as a generative AI that helps you break down and interpret what that data actually means. So while MIV allows you to quantify impact, this kind of qualitative layer helps you understand the substance behind it. For example, in all your fashion media coverage, were people describing your brand as ‘innovative’? Or ‘elegant’? Or ‘sexy’? Compared to the industry at large, were you 10% higher – or maybe 3% lower – than a direct competitor? So if your brand positioning is meant to be ‘young, fresh, cheeky,’ but the conversation is skewing toward ‘heritage’ – that tells you something. You might have had the highest MIV, but if the narrative doesn’t match your intent, that’s a brand alignment issue. We’re moving beyond quantitative metrics and starting to slice the data down to reveal what people are actually saying. Again, going beyond sentiment analysis, which is just ‘positive’ or ‘negative’, to something that can really guide action.

Presumably, that’s something you could apply to a celebrity – to an individual as well as a brand?

Absolutely. The qualitative metrics will look at four levels. First, the industry – for example, how is something like ‘sustainability’ perceived across the industry? Are we as an industry trending above or below average in how that value shows up? Then, brand perception – how your specific brand is seen. Third is campaign analysis – especially useful for brands running repositioning campaigns. It helps determine whether those campaigns actually landed the way they were intended. And finally, ambassador analysis – so yes, we can apply this to individuals, like celebrities or influencers, to understand what kind of brand attributes are being associated with them too.

‘Can Media Impact Value tell you a show had a bleak and sombre vibe? No. But what it can tell you is whether that vibe worked, if it was talked about.’

Tom Ford tripled its MIV in Paris this season, largely due to its own social channels, which is interesting considering there was minimal media presence at the show. Are brands in Paris better at leveraging their owned media compared to other cities? Or are we seeing similar strategies being used across all the fashion capitals?

This was interesting, because you had the percentage of owned media, and then I asked our comms team to also pull the average value per post – and it’s true, Paris is quite high. So yes, Paris in general has a high Media Impact Value. Paris Fashion Week as an event itself just gets a lot of attention – more eyeballs. So those brands are benefitting from the fact that there’s simply more attention on Paris than in other markets.

Brands like Vaquera and The Row have seen a significant boost in global awareness since showing at Paris Fashion Week. Paris feels like it’s operating on another level.

What’s interesting, though, is that New York still delivers strong MIV – even if its industry reputation doesn’t match Paris. It’s punching above its weight in terms of visibility. I’ve spoken to some of the federation partners across the different fashion weeks, and they’re seeing it too: more people are choosing Paris. I think, unfortunately, it’s partly that people don’t want to come to the US right now – whether that’s political, economic, or both. People are having to choose which fashion weeks they travel to, and Paris is the one you can’t miss. Even some of the brands we usually see showing or being covered in other markets – as you said, Vaquera, and there are certainly others – we’re seeing them in Paris now. So I think that shift is real. I do hope, as things improve economically, we’ll see the balance start to return. But this season in Paris, it felt like everything was happening at the same time. I don’t necessarily think that’s sustainable – for the people attending or for the city itself. It’s just too much. But again, if people are forced to choose, they’re never going to say, ‘I’m skipping Paris.’ Because Paris is fashion, and fashion is Paris.